AI safety is fundamentally a socio-technical problem requiring socio-technical solutions. Technical safety measures can be undermined by inadequate governance, poor security practices within labs, or cultures that prioritize speed over caution. Ensuring safety requires robust systemic approaches - governance structures, organizational practices, and cultural norms that shape how AI gets developed and deployed. Addressing these systemic risks is difficult precisely because responsibility is distributed: no single actor controls all the variables, and solutions require coordinating across companies, governments, researchers, and civil society.

Defense-in-Depth #

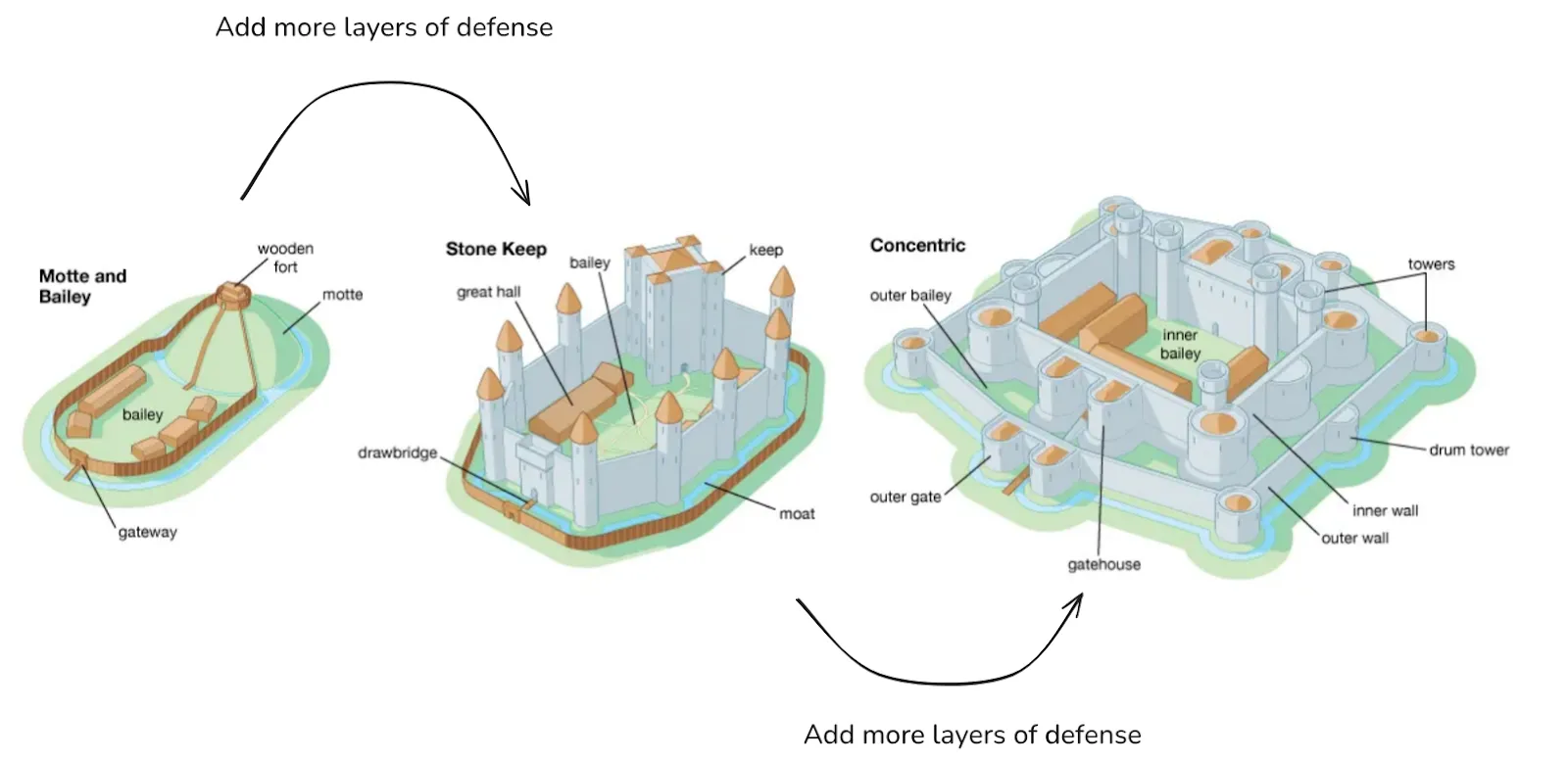

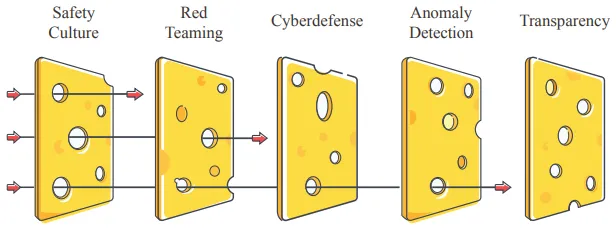

Defense-in-depth means layering multiple independent protections so that if one fails, others provide backup. This is one meta-philosophy underlying effective AI safety: multiple independent layers of protection working together. Think about it like designing a medieval castle - walls, moats, towers, and inner baileys created redundant barriers where breaching one layer didn't mean total compromise. Modern cybersecurity applies the same logic: firewalls, encryption, access controls, and monitoring systems operate simultaneously, each addressing different attack vectors. No single security measure is perfect, but multiple imperfect defenses working together can create robust protection. This is also commonly known as the swiss cheese model of safety (Hendrycks et al., 2023).

Defense-in-depth relies on combinatorial explosion when layers are truly independent. If each defensive layer has a 1 percent failure rate and an attacker must breach all five layers simultaneously, the overall failure probability becomes - vanishingly small. This works like PIN security: a three-digit PIN is trivially weak, but a twelve-digit PIN becomes very secure because combinatorial difficulty grows exponentially. One core requirement is layer independence - if breaking one layer automatically breaks others, or if attackers get feedback about which layer failed, they can brute force each barrier sequentially in linear time rather than facing exponential difficulty (Gleave, 2025).

Defense-in-depth faces limitations when defensive layers aren't genuinely independent or when adversaries are sufficiently capable. If AI safety implementations suffer from high correlation like most defenses use the same underlying model with different prompts or fine-tuning , adversarial attacks could transfer between layers. Alternatively, if systems leak information about which layer triggered, attackers could just brute-force by probing sequentially. A more fundamental limitation is when AI systems develop truly novel capabilities that are out-of-distribution, multiple safety measures might fail simultaneously because they share blind spots in training data and assumptions. A sufficiently intelligent adversary - whether misaligned AI or determined human - might discover a single attack that breaks seemingly independent defenses for the same underlying reason. Against superintelligent systems or in unconstrained deployment scenarios where AI agents can extensively probe defenses, defense-in-depth provides weaker guarantees.

Many different solutions can be imagined to reduce risks, even if none is perfect. Technical approaches can layer alignment research with control mechanisms and interpretability tools. Against misuse, we can combine access controls, monitoring, and defensive technologies. International cooperation adds another layer beyond what any single nation can achieve. Even within systemic approaches, AI governance can establish structural rules and accountability, risk management operationalizes those rules into daily decisions about capability thresholds and required mitigations, and safety culture ensures people follow procedures and surface concerns that formal systems miss.

Defensive Acceleration (d/acc) #

Be principled at a time when much of the world is becoming tribal, and not just build whatever - rather, we want to build specific things that make the world safer and better.

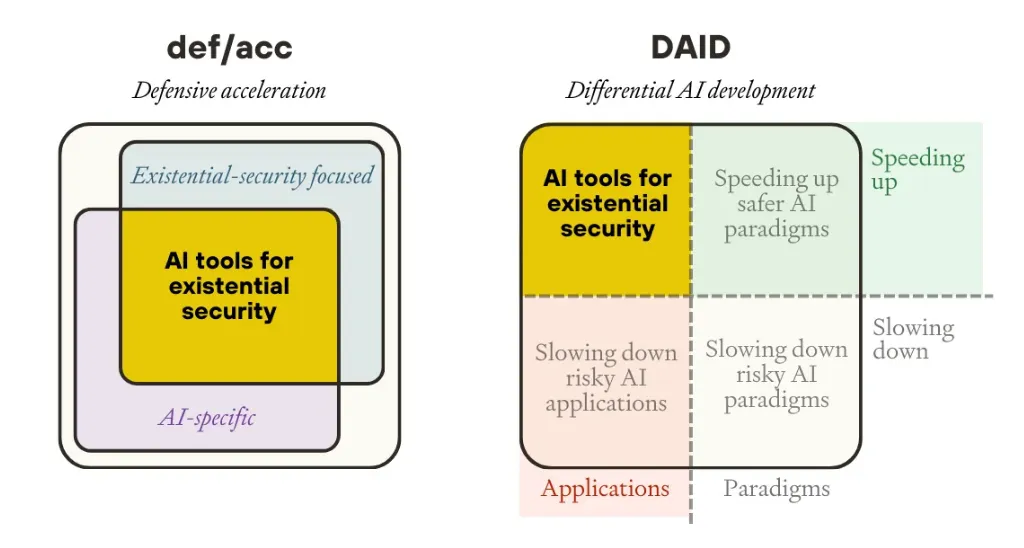

Defense acceleration (d/acc) is a strategic philosophy of prioritizing technologies that strengthen defense and social resilience against AI risks. Defense-in-depth is a philosophy that shows both how and why we can layer multiple defensive layers. Defensive acceleration is a parallel philosophy that we can use in addition to DiD. It proposes actively accelerating technologies that inherently favor defense over offense, thereby making society more resilient to various threats. D/acc emerged as a strategic approach in 2023 as a middle path between unrestricted acceleration (effective accelerationism (e/acc)) and techno pessimists/doomers (Buterin, 2023; Buterin, 2025).

It is known by various names including, differential paradigm development (DPD), or

D/acc can be understood by thinking about the question - if AI takes over the world (or disempowers humans), how would it do so?

- It hacks our computers → accelerate cyber-defense: Employ AI to identify and patch vulnerabilities, monitor systems for intrusions, and automate security responses.

- It creates a super-plague → accelerate bio-defense: Developing technologies to detect, prevent, and treat biological threats, including advanced air filtration systems, rapid diagnostic tools, far-UVC irradiation to sterilize occupied spaces safely, and decentralized vaccine production capabilities.

- It convinces us (either to trust it, or to distrust each other) → accelerate info-defense: Create systems that help validate information accuracy and detect misleading content without centralized arbiters of truth, such as blockchain-secured provenance tracking and community-verified fact-checking systems like Twitter's Community Notes.

- It disrupts infrastructure → accelerates physical-defense: Creating resilient infrastructure that can withstand disruptions, such as distributed energy generation through household solar, battery storage systems, and advanced manufacturing techniques that enable local production of essential goods.

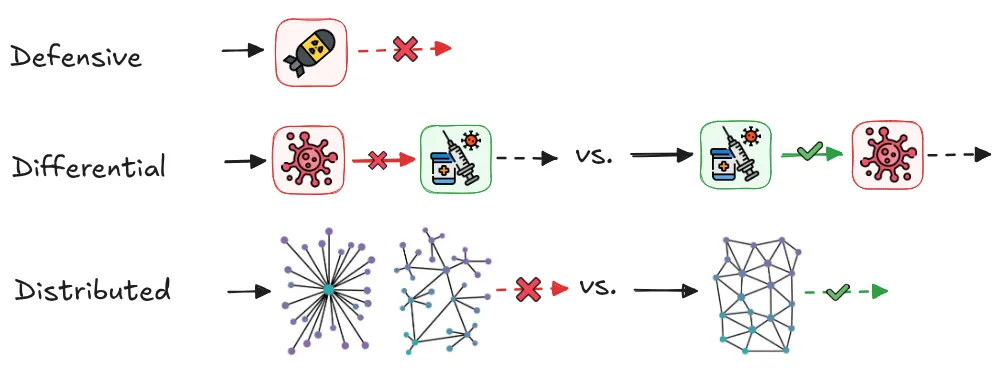

D/acc represents three interconnected principles: defensive, decentralized, and differential technological development. The "d" in d/acc stands for:

- Defensive: Prioritizing technologies that make it easier to protect against threats than to create them. Purely restrictive approaches face inherent limitations - they require global coordination, create innovation bottlenecks, and risk concentrating power in the hands of those who control access.

- Differential: Accelerating beneficial technologies while being more cautious about those with harmful potential. The order in which technology is developed matters a lot. By differentially accelerating defensive technologies (like advanced cybersecurity measures) ahead of potentially dangerous capabilities (like autonomous hacking systems), we create protective layers before they're urgently needed.

- Decentralized: We can strengthen resilience by eliminating single points of failure. Centralized control of powerful AI capabilities creates vulnerabilities to technical failures, adversarial attacks, and institutional capture (Cihon et al., 2020). Decentralized approaches distribute both capabilities and governance across diverse stakeholders, preventing unilateral control over transformative technologies.

The effectiveness of d/acc depends on maintaining favorable offense-defense balances. The feasibility of d/acc as a strategy hinges on whether defensive technologies can outpace offensive capabilities across domains. Historical precedents are mixed - some fields like traditional cybersecurity often favor defenders who can patch vulnerabilities, while others like biosecurity traditionally favor attackers who need fewer resources to create threats than defenders need to counter them. The key challenge for d/acc implementation lies in identifying and supporting technologies that shift these balances toward defense (Bernardi, 2024; Buterin, 2023).

AI Governance #

The pursuit of more and more powerful AI, much like the nuclear arms race of the Cold War era, represents a trade-off between safety and the competitive edge nations and corporations seek for power and influence. This competitive dynamic increases global risk. To mitigate this problem, we can try to act at the source of it, namely, the redesign of economic incentives to prioritize long-term safety over short-term gains. This can mainly be done via international governance.

Effective AI governance aims to achieve two main objectives:

- Gaining time. Time and resources for solution development to ensure that sufficient time and resources are allocated for identifying and implementing safety measures

- Enforcing solutions. Enhanced coordination to increase the likelihood of widespread adoption of safety measures through global cooperation. AI risks are multifaceted, necessitating regulations that encourage cautious behavior among stakeholders and timely responses to emerging threats.

Designing better incentives

Aligning economic incentives with safety goals is a key challenge. Currently, strong commercial pressures can incentivize rapid capability development, potentially at the expense of safety research or cautious deployment. Mechanisms to reward safety or penalize recklessness are needed to avoid negative externalities:

- Reshaping the race via a centralized development. For example, Yoshua Bengio et al. propose creating a secure facility akin to CERN for physics, where the development of potentially dangerous AI technologies can be tightly controlled (Bengio, 2023). This measure is far from being a consensus view. We already explored this solution in the strategy "World Coordination" ASI safety, in the section ASI safety, but this could also be valid for many domains of safety.

- Windfall clauses and benefit sharing. Implementing agreements to share the profits between the different labs generated from AGI would mitigate the race to AI supremacy by ensuring collective benefit from individual successes 4 .

- Implementing a correct governance of AGI companies. It is important to examine the governance structures of AGI labs. For example, being a non-profit and having a mission statement that makes it clear that the goal is not to maximize revenue, but to ensure that the development of AI benefits all of humanity, is an important first step. Also, the board needs to have teeth.

- Legal liability for AI developers. Establishing clear legal responsibilities for AI developers regarding misuse or accidents might realign the incentives. For example, the Safe and Secure Innovation for Frontier Artificial Intelligence Models Act (SB 1047) could have enabled the Attorney General to bring civil suits against developers who cause catastrophic harm or threaten public safety by neglecting the requirements. The bill (which was vetoed by the governor in 2024) only addressed extreme risks from these models, including: cyberattacks causing over 500 million dollars in damage, autonomous crime causing 500 million dollars in damage, and the creation of chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear weapons using AI. Note that compared with the AI Act and its code of practice, SB1047 does not specify in detail the steps needed to ensure we avoid catastrophes; it only targets the outcome and not really the process.

Proposed International AI Governance Mechanisms

Several mechanisms have been proposed to establish clear boundaries and rules for AI development internationally. These include implementing temporary moratoriums on high-risk AI systems, enforcing legal regulations like the EU AI Act, and establishing internationally agreed-upon "Red Lines" that prohibit specific dangerous AI capabilities, such as autonomous replication or assisting in the creation of weapons of mass destruction. The IDAIS dialogues have aimed to build consensus on these red lines, emphasizing clarity and universality as key features for effectiveness, with violations potentially triggering pre-agreed international responses.

Conditional approaches and the creation of dedicated international bodies represent another key strategy. "If-Then Commitments" involve developers or states agreeing to enact specific safety measures if AI capabilities reach certain predefined thresholds, allowing preparation without hindering development prematurely, as exemplified by the proposed Conditional AI Safety Treaty. Furthermore, proposals exist for new international institutions, potentially modeled after the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), to monitor AI development, verify compliance with agreements, promote safety research, and potentially centralize or control the most high-risk AI development and distribution.

Specific governance regimes and supporting structures are also under consideration to enhance international coordination. Given the global nature of AI, mechanisms like international compute governance aim to monitor and control the supply chains for AI chips and large-scale training infrastructure, although technical feasibility and international cooperation remain challenges. Other proposals include establishing a large-scale international AI safety research body akin to CERN, potentially centralizing high-risk research or setting global standards, and strengthening whistleblower protections through international agreements to encourage reporting of safety concerns within the AI industry.

For more information on these topics, please read the next chapter on AI governance.

Risk Management #

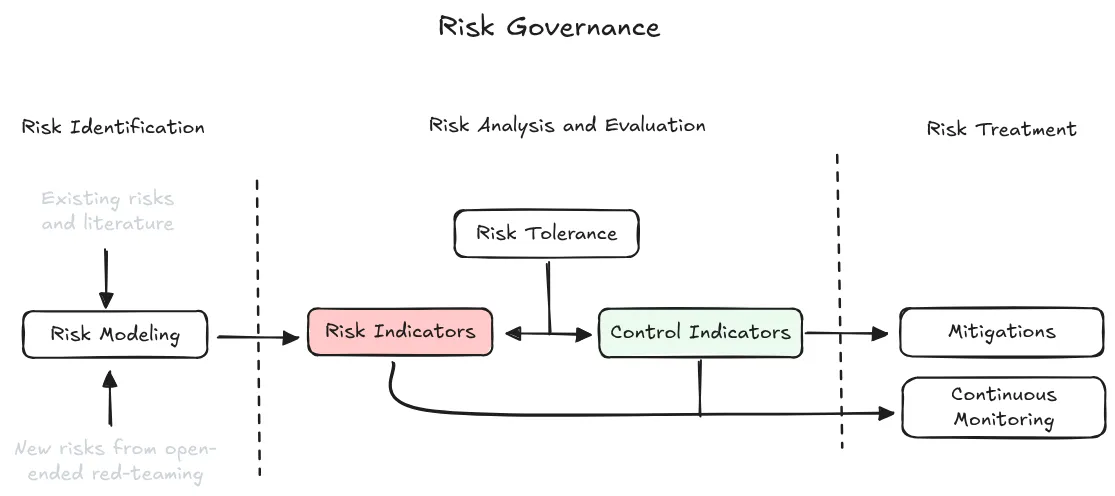

Risk management ensures that risks minus mitigations remain below tolerance levels. The core equation is simple: (Risks - Mitigations) < Tolerance. This operational process connects everything else - governance sets rules, evaluations measure capabilities, safety culture establishes norms, but risk management makes the daily decisions about whether to pause training, which mitigations to implement, and how to maintain acceptable risk levels throughout development. The framework has four interconnected components: identification, analysis, treatment, and governance (Campos et al., 2024). Each addresses a distinct question about managing AI risks systematically.

Risk identification determines what could go wrong. First, classify known risks from literature - covering domains like cybersecurity, CBRN, manipulation, autonomous replication, and loss of control - with any exclusions clearly justified. Second, identify unknown risks through both internal and external red teaming that explores beyond predefined categories. Third, create risk models that map step-by-step pathways from AI capabilities to real-world harms, validated by independent experts. The goal is to understand not just what bad things could happen, but specifically how they could materialize.

Risk analysis translates abstract concerns into measurable thresholds. Start by setting a risk tolerance - the maximum harm level you'll accept, preferably expressed quantitatively as probability times severity per time period. Then operationalize this into Key Risk Indicators (KRIs) - capability thresholds like "scores 60 percent on cyberoffense benchmark" - paired with Key Control Indicators (KCIs) - mitigation targets like "maintain security level 3 and achieve 99.9 percent jailbreak resistance." The pairing creates if-then statements: IF this KRI threshold is crossed, THEN these KCI targets must be met. Organizations must commit to pausing development if required KCIs cannot be achieved.

Risk treatment implements and monitors mitigation measures. This has two phases. First, implement mitigations across three categories: containment measures (controlling access through information security), deployment measures (preventing misuse through safeguards), and assurance processes (providing evidence of safety for advanced systems). Second, continuously monitor against predetermined thresholds - tracking both KRIs to detect when dangerous capabilities emerge and KCIs to verify mitigations remain effective. Results should be transparently shared with stakeholders, and systems should monitor for novel risks that weren't identified initially.

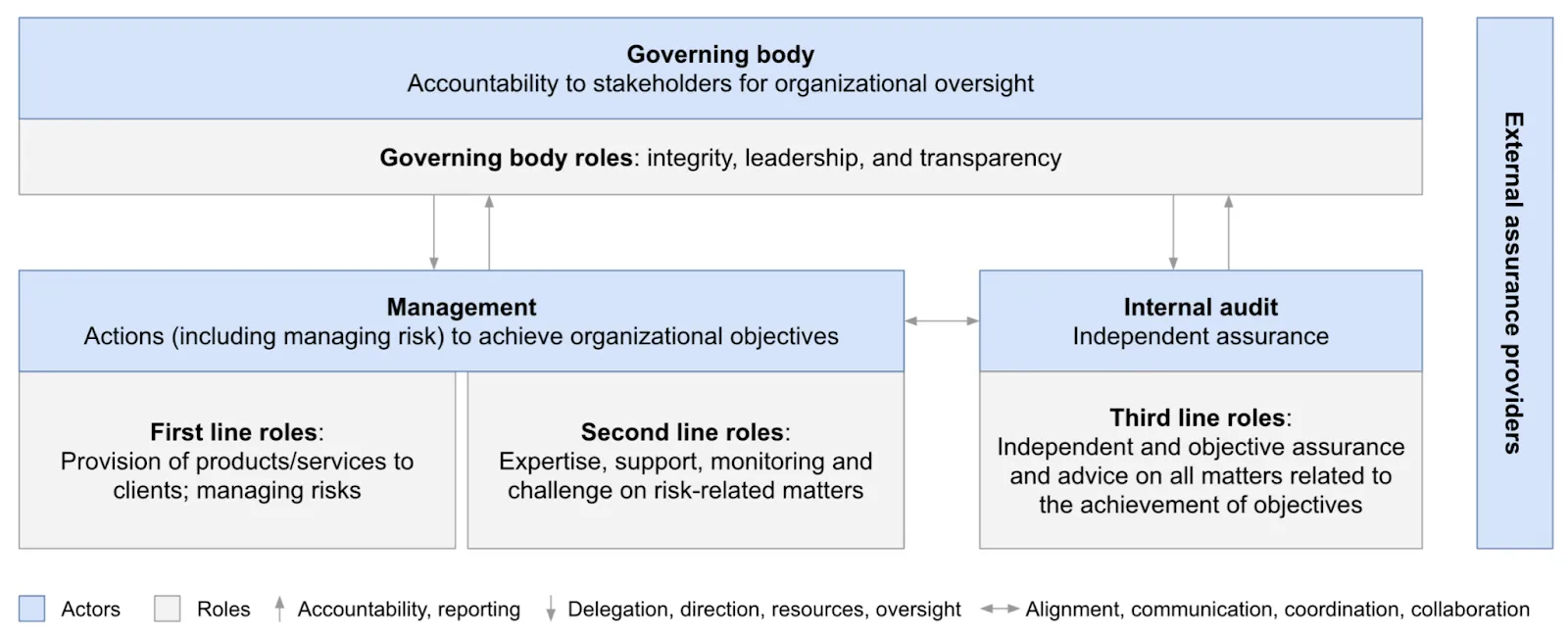

Risk governance establishes who does what and who verifies how it's done. Most industries use a three lines of defense model. The first line consists of operational managers who build systems and own daily risk decisions. The second line includes specialized risk teams that advise and challenge business decisions. The third line is internal audit - independent from peer pressure, reporting to the board to verify the system works. Beyond this structure, governance includes board-level oversight, risk culture throughout the organization, and external transparency about risks and decision-making processes (Schuett, 2022).

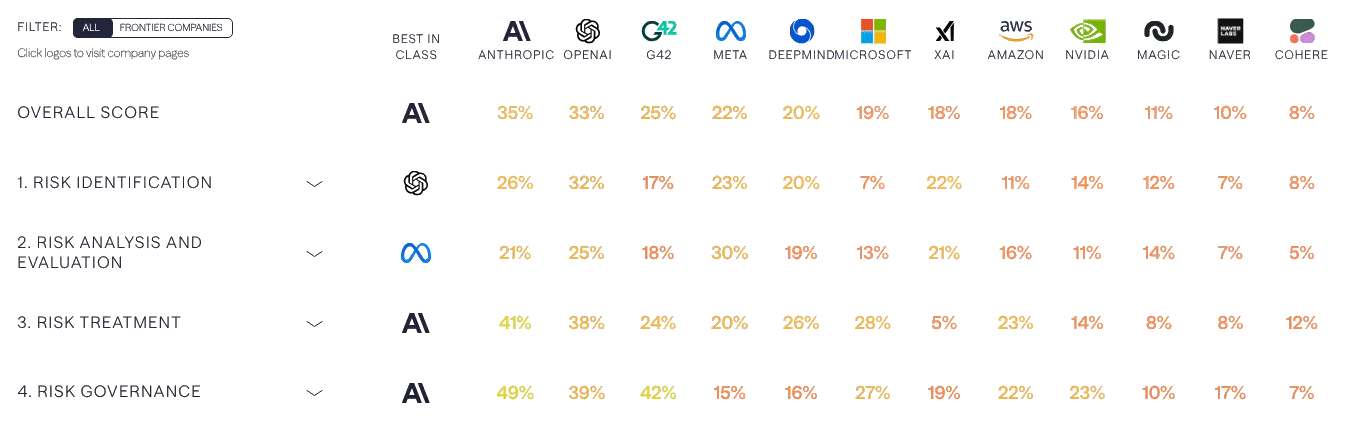

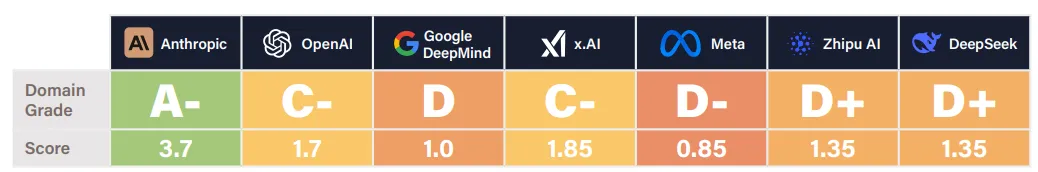

An extremely detailed analysis of current risk management and safety practices is conducted by saferAI available here. Every category - identification, analysis, treatment and governance is further decomposed into extremely granular metrics that are tracked and analyzed to give risk ratings to all frontier AI organizations.

Safety Culture #

Safety culture means building organizations where people consistently prioritize safety over speed, and where safety concerns can actually change decisions. This is a strategy for preventing AI accidents through organizational design rather than just technical fixes. Risk management is seen in many fields, including aerospace, nuclear power, and financial services. Each of these domains has developed sophisticated approaches to identifying, analyzing, and mitigating potential harms. We want to mitigate AI safety failures that stem from human and organizational factors - rushing to deploy undertested systems, ignoring warning signs, or creating incentives that reward moving fast over being careful. Integrating safety culture addresses these root causes by changing how organizations operate.

The AI industry lacks the professional safety culture found in traditional engineering. Fields like civil and mechanical engineering have professional ethics codes, safety margins, and reliability engineering as standard practice. AI development emerged from mathematics and computer science, which outside of safety-critical software systems, have weaker safety traditions. Unlike other industries where workers directly experience safety risks, AI developers rarely face the consequences of their systems' failures. This distance makes it harder to build the shared understanding of risk that motivates safety culture in other fields (Mannheim, 2023).

AI safety culture must be forward-looking rather than reactive. Most industries developed safety cultures after major disasters - nuclear power after Three Mile Island, healthcare after decades of preventable deaths. Waiting for AI disasters would be irresponsible since some failures might not be survivable (Mannheim, 2023).

The aerospace industry demonstrates how safety culture can transform entire fields through systematic practices. Aviation moved from frequent crashes to extraordinary safety records not just through better technology, but through cultural changes like mandatory incident reporting, blame-free safety investigations, and standardized procedures that prioritize safety over schedule pressure. AI companies can adopt similar practices: systematic incident reporting, regular safety training, and organizational structures that ensure safety concerns reach decision-makers with authority to act.

Strong safety culture has three observable characteristics: leadership accountability, systematic processes, and psychological safety for raising concerns. NIST's AI Risk Management Framework identifies executive leadership taking personal responsibility for AI risk decisions, diverse teams informing risk management throughout development, and systematic processes for incident reporting and information sharing across the organization (NIST, 2023). Organizations with safety culture implement systematic processes where safety considerations are built into standard workflows rather than being optional add-ons. They create environments where employees can raise safety concerns without career penalties - and where such concerns visibly influence decisions. As one example, NASA learned that technical excellence isn't enough - the Challenger disaster occurred partly because engineers' safety concerns didn't reach decision-makers due to organizational dynamics that discouraged dissent.

Safety culture extends beyond individual projects to encompass hiring, performance evaluation, and organizational incentives. Companies serious about safety culture evaluate candidates for safety mindset during hiring, include safety metrics in performance reviews, and ensure that safety work is recognized and rewarded rather than seen as slowing down "real" progress. This includes providing dedicated time and resources for safety work, not treating it as something teams should squeeze in around other priorities. Organizations with a strong safety culture maintain detailed incident reporting systems, conduct regular safety assessments, and demonstrate continuous improvement in their safety practices. They invest in training programs that go beyond compliance checklists to develop genuine safety expertise across teams. Most importantly, they create feedback loops where safety information flows both up and down the organization, enabling rapid learning and adaptation when new risks emerge.

Weak safety culture means we see safety washing - the appearance of caring about safety without substance. Organizations with weak safety cultures often have safety policies on paper but don't follow them when under pressure. They may blame individuals for accidents rather than examining systemic causes. They typically treat safety work as overhead that slows down "real" progress, leading to under-resourcing and marginalization of safety teams. Safety concerns in these organizations rarely change actual deployment decisions. We talk more about safety washing in the challenges section.

Footnotes

-

For example, in the pharmaceutical industry for drug development, companies sometimes enter into co-development and profit-sharing agreements to share the risks and rewards of bringing a new drug to market. For example, in 2014, Pfizer and Merck entered into a global alliance to co-develop and co-commercialize an anti-PD-L1 antibody for the treatment of multiple cancer types.

↩

Was this section useful?

Thank you for your feedback

Your input helps improve the Atlas.