In the previous section, we looked at different notions of how to define AGI and measure the relevant capabilities. Now we'll examine one of the most important drivers behind improvements in these capabilities: scale.

Bitter Lesson #

Human-engineered domain knowledge consistently loses to general methods that leverage massive computation. We assume that most of you probably went to university in an era where machine learning and AI roughly mean the same thing, or even that deep learning and AI mean the same thing. This hasn't always been true. Early in AI's history, researchers believed the key to artificial intelligence was carefully encoding human knowledge and expertise into computer programs. This led to expert systems filled with hand-crafted rules and chess engines programmed with sophisticated strategic principles. Time and again, these approaches hit walls while simple learning algorithms combined with massive computation kept improving. However, time and time again, researchers learned what we now call the bitter lesson.

The biggest lesson that can be read from 70 years of AI research is that general methods that leverage computation are ultimately the most effective, and by a large margin. [...] The bitter lesson is based on the historical observations that 1) AI researchers have often tried to build knowledge into their agents, 2) this always helps in the short term, and is personally satisfying to the researcher, but 3) in the long run it plateaus and even inhibits further progress, and 4) breakthrough progress eventually arrives by an opposing approach based on scaling computation by search and learning.

The bitterness comes from discovering that decades of human expertise mattered less than computation. Researchers who spent years encoding grandmaster chess knowledge watched brute-force search defeat world champion Garry Kasparov. Hand-crafted feature detectors in computer vision got outperformed by neural networks that learned their own features from data. Phonetics-based speech recognition lost to statistical approaches. The pattern repeated: domain expertise helped initially, then hit a wall. Simple learning algorithms plus massive compute kept improving (Sutton, 2019).

The bitter lesson doesn't reject human ingenuity or algorithmic innovation. There's a difference between building better general learning systems and encoding task-specific human knowledge. This isn’t a difference just between good old fashion AI (GoFAI), and modern deep learning . Even within deep learning , the bitter lesson still applies—the winning algorithms are those that leverage scale most effectively. Transformers didn't beat LSTMs by encoding linguistic knowledge. They outperformed because attention mechanisms parallelize better and can actually use massive compute productively. Algorithmic innovation still matters - finding architectures and training methods that extract more from the same data and hardware. The algorithms that succeed are the ones that unlock scale's potential.

The bitter lesson shapes expectations about AI progress. If the bitter lesson continues to be true, improvements should come from either finding algorithms that better leverage scale, or simply scaling existing algorithms with more compute, data, and parameters. In the last few years, the majority of gains seen in AI capabilities have emerged from scaling up the same transformer based language models.

Scaling Laws #

Training frontier AI models costs hundreds of millions of dollars, making it critical to predict returns on investment. AI labs face resource allocation decisions with massive stakes: should they spend more on GPUs or training data ? Train a larger model briefly or a smaller model longer? With a fixed compute budget, they might choose between a 20-billion parameter model trained on 40% of their data or a 200-billion parameter model trained on 4% of it. Getting this wrong wastes hundreds of millions. Scaling laws help turn these gambles into engineering decisions by establishing empirically observed relationships between inputs and model accuracy.

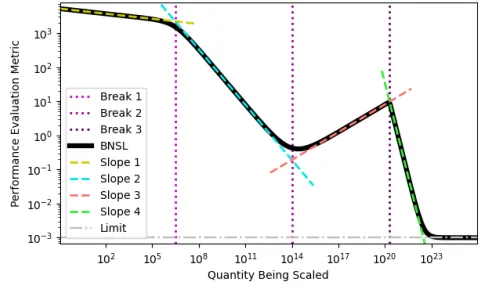

Scaling laws describe how model accuracy changes as you vary four key variables:

- Compute: Total floating-point operations (FLOPs) during training - accounts for GPU power, number of chips, and training duration (how many steps you train for).

- Parameters: The numbers the model adjusts during training - roughly analogous to "model size".

- Data: Training examples seen, measured in tokens for LLMs.

- Accuracy: How well the model performs on benchmarks - the inverse of "loss" (lower loss = higher accuracy).

Scaling laws are empirically observed relationships, not laws of nature. OpenAI first documented these relationships in 2020 by running hundreds of experiments, varying inputs while measuring accuracy (Kaplan et al., 2020). They found that when you increase compute by 10×, accuracy improves predictably. Double the parameters, accuracy jumps predictably. These patterns proved surprisingly consistent across model architectures and tasks, suggesting they capture something fundamental about how neural networks learn. Later research revealed optimal training requires roughly 20 tokens of data per parameter - about 10× more data than early laws suggested 5 (Hoffmann et al., 2022). This meant previous large models were undertrained relative to their size. The relationships continue evolving as researchers gather more evidence, but the core insight remains: scale drives predictable capability gains. The following graphs clearly show massive increases in scale for data, compute, and parameter count by all major AI labs.

Scaling Hypothesis #

Scaling might continue driving capability gains. Look back at the examples from previous sections - the programming abilities, emergent reasoning, scientific research assistance, the jump from GPT-3.5 to GPT-4 across professional exams. These capabilities appeared as models got bigger and trained on more data, without requiring new architectural breakthroughs or encoded domain knowledge. If current approaches scaled up could produce systems capable of automating AI research within years, safety work becomes far more urgent. The existing evidence supports multiple interpretations because we're watching a technology develop in real-time whose limits we don't fully understand. So different people hold different hypotheses about how the future could unfold.

The strong scaling hypothesis. This proposes that simply scaling up existing architectures with more compute and data will be sufficient to reach transformative AI capabilities (Gwern, 2020). According to this view, we already have all the fundamental components needed - it's just a matter of making them bigger, following established scaling laws.

The weak scaling hypothesis. This view states that even though scale will continue to be the primary driver of progress, we will also need targeted architectural and algorithmic improvements to overcome specific bottlenecks. These improvements wouldn't require fundamental breakthroughs, but rather incremental enhancements to better leverage scale (Gwern, 2020).

Researchers have been developing algorithms that leverage scale and compute for more than a decade. We have seen many gains come from improvement in compute efficiency from innovations like better attention mechanisms, mixture-of-experts routing, and efficient training methods. But even when researchers have developed sophisticated algorithms following the bitter lesson's principles, data suggests that between 60-95% of performance gains came from scaling compute and data. While algorithmic improvements contributed 5-40%, though there is substantial methodological uncertainty in disentangling these contributions (Ho et al., 2024).

The emergence of unexpected capabilities might provide another argument for strong scaling. We've seen previous generations of foundation models demonstrate remarkable abilities that weren't explicitly trained for, like programming. This emergent behavior hints that it is not impossible for higher-order cognitive abilities to similarly emerge simply as a function of further scale.

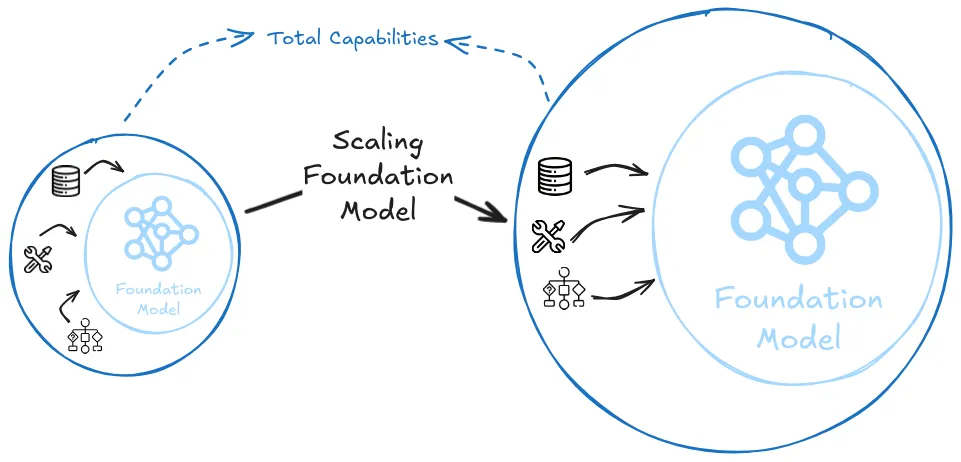

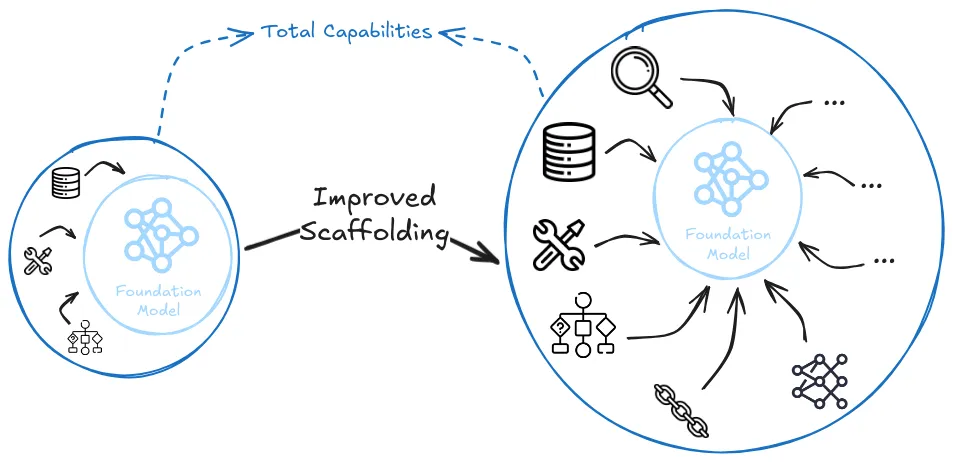

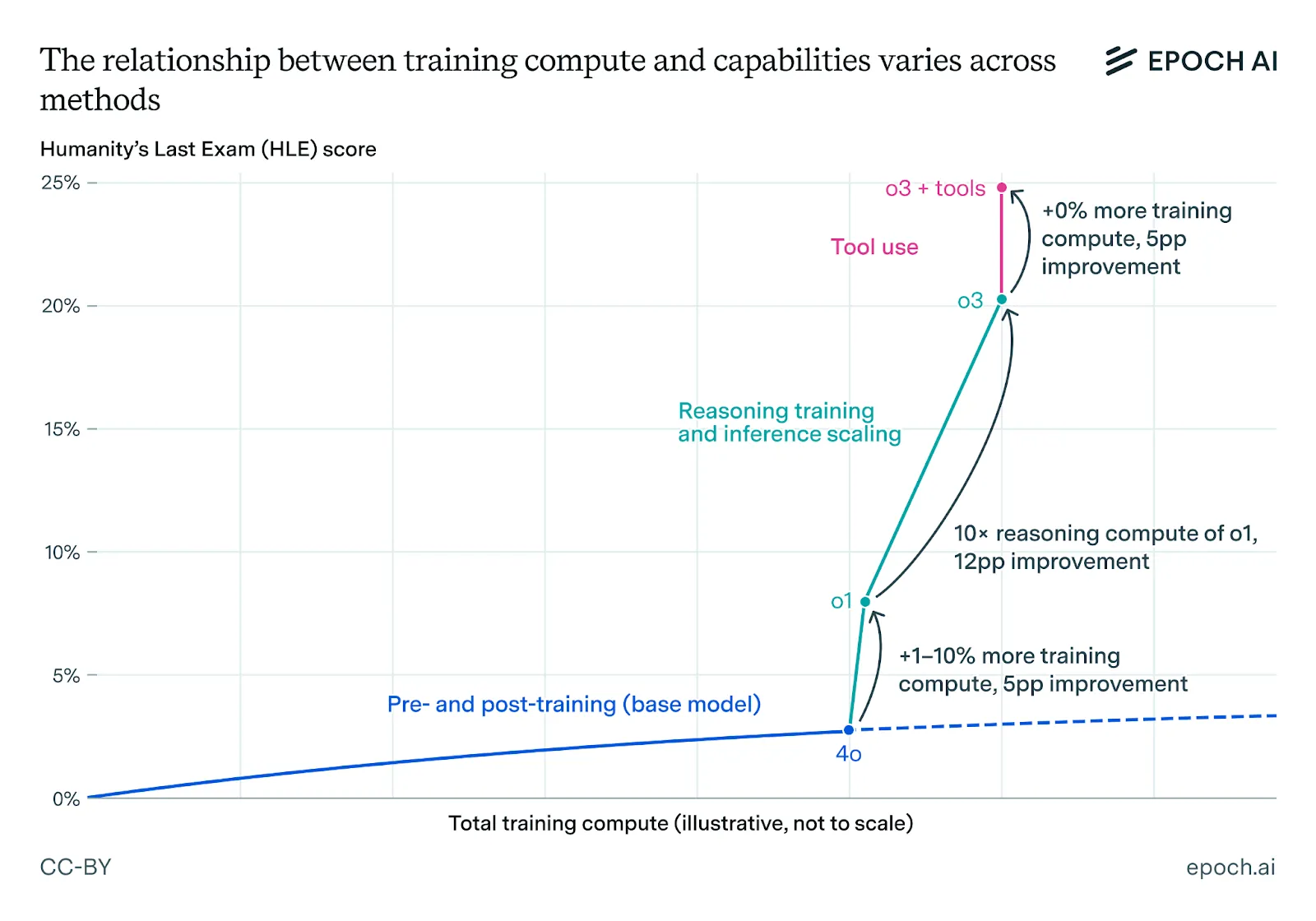

Scale combined with techniques and tools hypothesis. Essentially, both the scaling laws (which only predict foundation model capabilities) and most debates around "scale is all you need" often miss other aspects of AI development that happen outside the scope of what scaling laws can predict. They don't account for improvements in AI "scaffolding" (like chain-of-thought prompting, tool use, or retrieval), or combinations of multiple models working together in novel ways. Any LLM with internet access, code execution, and the ability to call upon the help of other specialized sub-models has substantially more capability than the same LLM alone. We gave several examples of this being the dominant trend in our first section - tool use, thinking for longer (inference time scaling), MCP servers and so on.

Debates around the scaling laws only tell us about the capabilities of a single foundation model trained in a standard way. For example, by the strong scaling hypothesis we can reach TAI by simply scaling up the same foundation model until it completely automates ML RnD. But even if scaling stops, halting capabilities progress on the core foundation model (in either a weak or a strong way), the external techniques that leverage the existing model can still continue advancing. Many researchers think that this is a core element where future capabilities will come from. It is also referred to as "unhobbling" (Aschenbrenner, 2024), "schlep" (Cotra, 2023) and various other terms, but all of them point to the same underlying principle - raw scaling of single model performance is only one part of overall AI capability advancement.

Even the tool based scaling hypothesis is debated. Some argue that tools or scale poured into LLMs is unlikely to lead to AGI as they define it. They advocate for completely different architectures from transformer based LLMs, focusing instead on things like neuro-symbolic approaches, ensemble methods, or a completely new undiscovered architecture (Goertzel et. al., 2023; Marcus, 2025; LeCun, 2025; Chollet, 2025).

Despite disagreements about whether scale will lead to “true AGI”, major AI labs are betting heavily on scaling. Sam Altman from OpenAI has stated his belief that scaling is going to be a big component leading to capability gains (Altman, 2023), Anthropic CEO Dario Amodei has expressed similar views (Amodei, 2023) and DeepMind's safety team similarly wrote that "not many more fundamental innovations are needed for AGI" (DeepMind, 2022). This consensus suggests that regardless of whether strong, weak, or tools-based scaling dominates, scale itself will likely remain central to near-term progress.

Footnotes

-

This is also commonly called ‘chinchilla optimality’ or the chinchilla optimal frontier based on the original model that these laws were tested on.

↩

Was this section useful?

Thank you for your feedback

Your input helps improve the Atlas.