Race dynamics #

[Talking about times near the creation of the first AGI] you have the race dynamics where everyone's trying to stay ahead, and that might require compromising on safety. So I think you would probably need some coordination among the larger entities that are doing this kind of training [...] Pause either further training, or pause deployment, or avoiding certain types of training that we think might be riskier.

We already talked about race dynamics in the chapter on AI risks as amplifying factors for all risks. We mention them here again, because governance initiatives might have special leverage to be able to mitigate race dynamics.

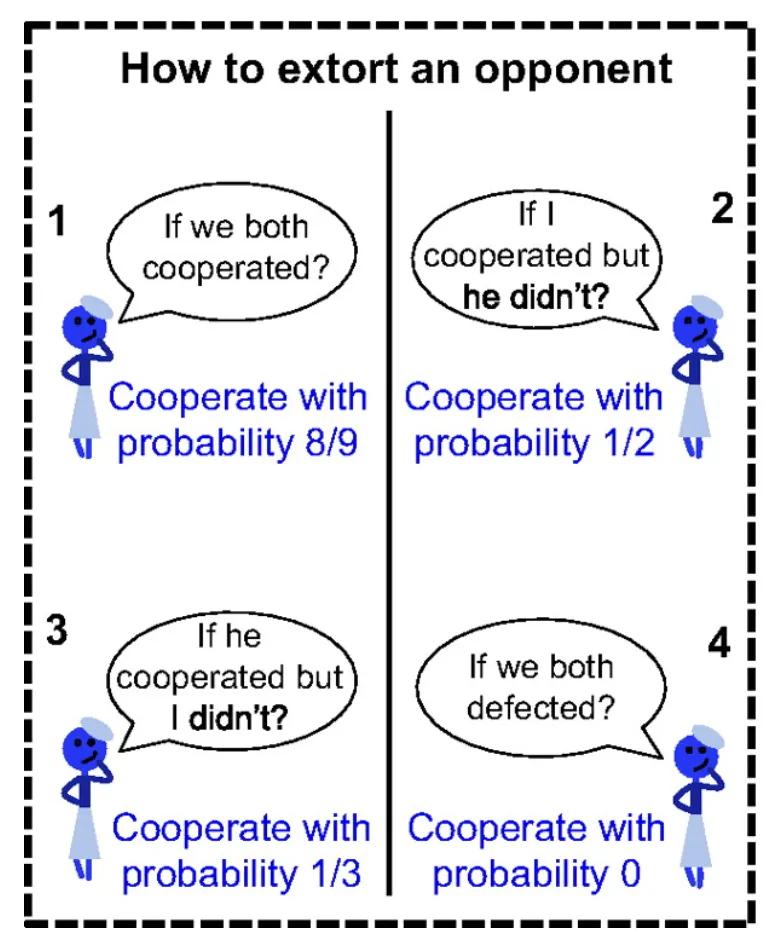

Competition drives AI development at every level. From startups racing to demonstrate new capabilities to nation-states viewing AI leadership as essential for future power, competitive pressures shape how AI systems are built and deployed. This dynamic creates a prisoners dilemma like tension where even though everyone would benefit from careful, safety-focused development, those who move fastest gain competitive advantage (Hendryks, 2024).

The AI race creates a collective action problem. Even when developers recognize risks, unilateral caution means ceding ground to less scrupulous competitors. OpenAI's evolution illustrates this tension: founded as a safety-focused small nonprofit, competitive pressures led to creating a for-profit subsidiary and accelerating deployment timelines. When your competitors are raising billions and shipping products monthly, taking six extra months for safety testing feels like falling irreversibly behind (Gruetzemacher et al., 2024). This dynamic makes it exceedingly difficult for any single entity, be it a company or a country, to prioritize safety over speed (Askell et al., 2019).

Competitive pressure leads to safetywashing, cutting corners on testing, skipping external red-teaming, and rationalizing away warning signs. "Move fast and break things" becomes the implicit motto, even when the things being broken might include fundamental safety guarantees. We've already seen this with models released despite known vulnerabilities, justified by the need to maintain market position. Public companies face constant pressure to demonstrate progress to investors. Each competitor's breakthrough becomes an existential threat requiring immediate response. When Anthropic releases Claude 3, OpenAI must respond with GPT-4.5. When Google demonstrates new capabilities, everyone scrambles to match them. This quarter-by-quarter racing leaves little room for careful safety work that might take years to pay off.

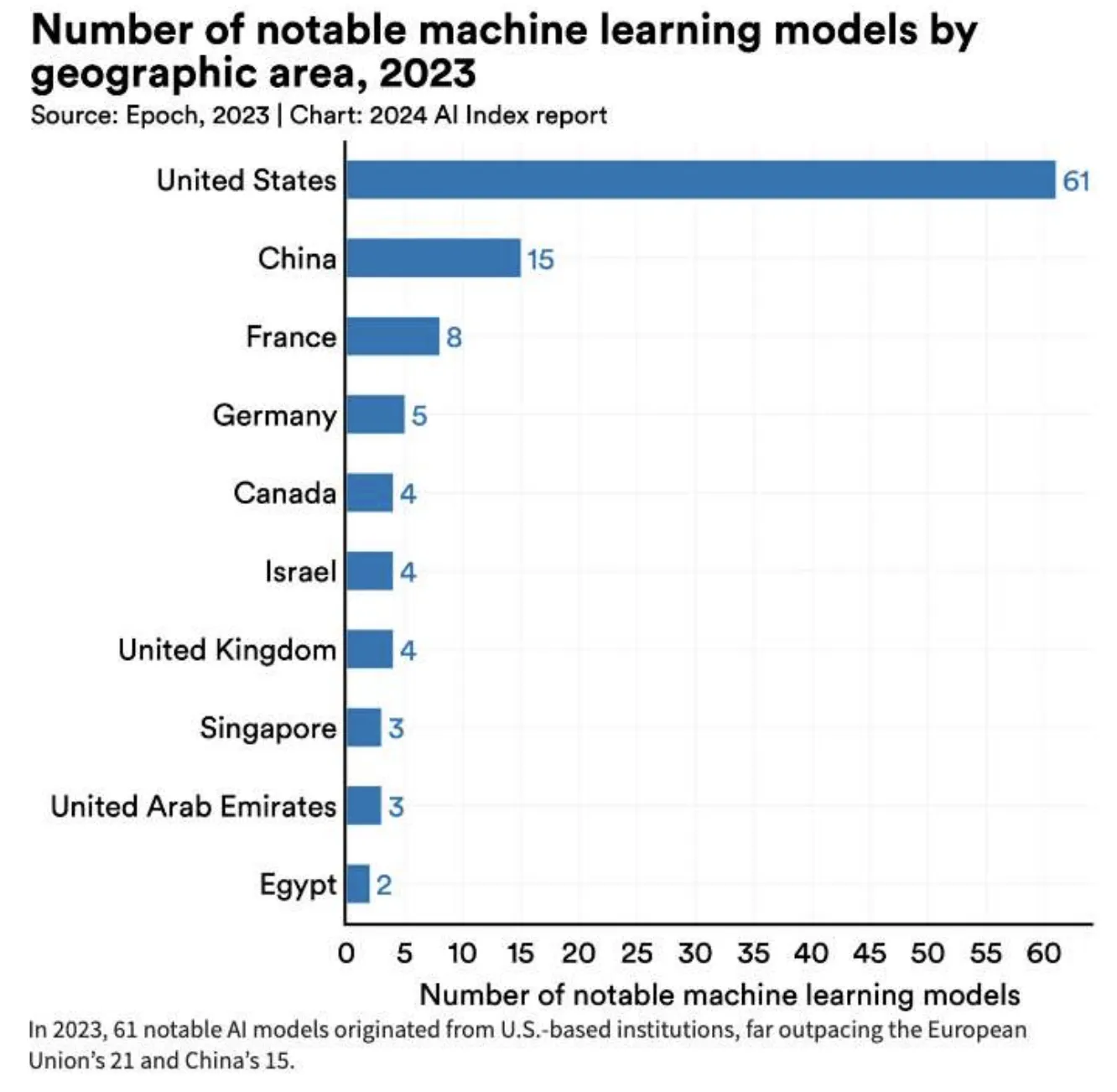

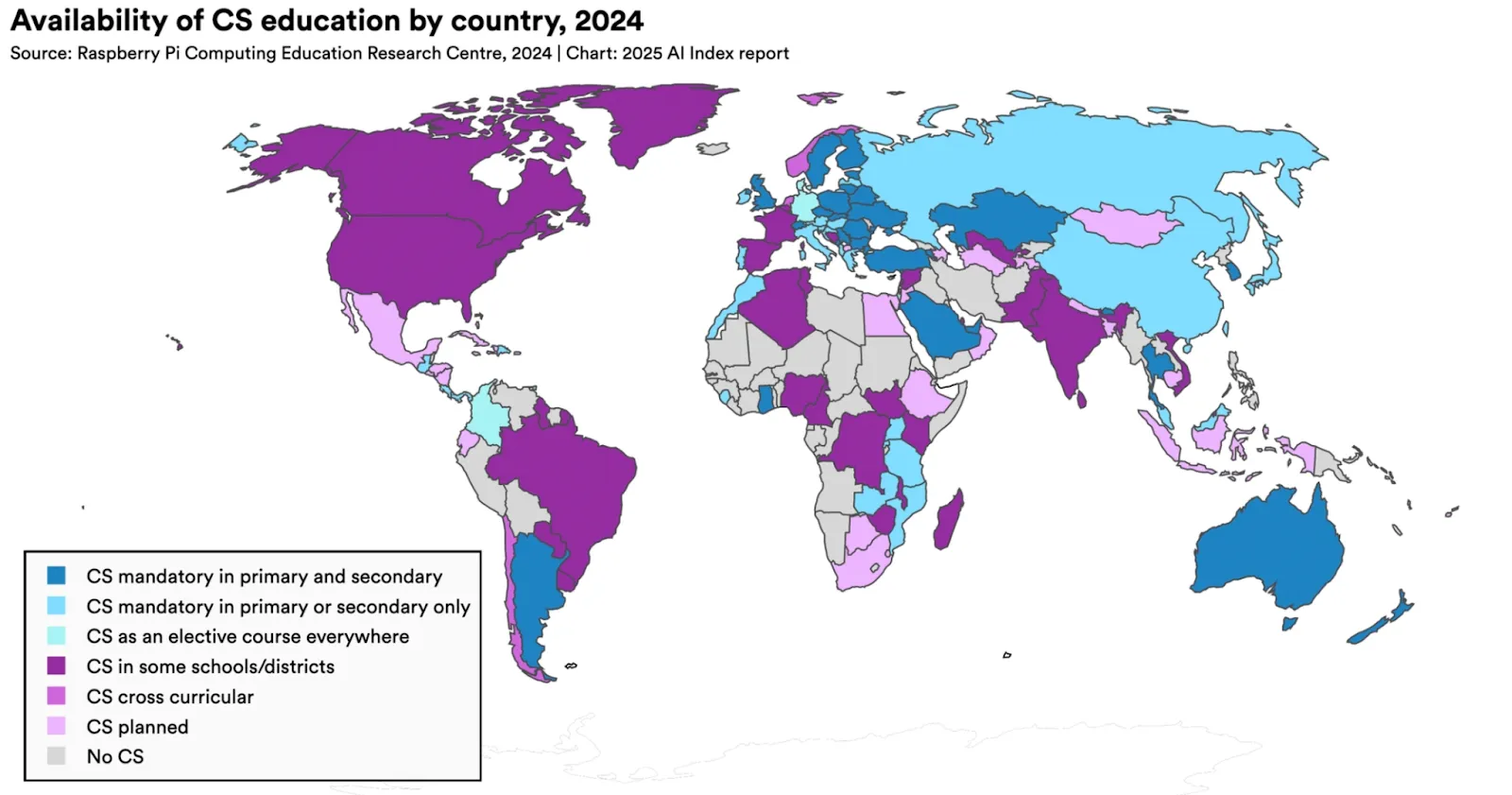

National security concerns intensify race dynamics. When Vladimir Putin declared "whoever becomes the leader in AI will become the ruler of the world," he articulated what many policymakers privately believe (AP News, 2017). This transforms AI development from a commercial competition into a perceived struggle for geopolitical dominance. Over 50 countries have launched national AI strategies, often explicitly framing AI leadership as critical for economic and military superiority (Stanford HAI, 2024; Stanford HAI, 2025). Unlike corporate races measured in product cycles, international AI competition involves long-term strategic positioning. Yet paradoxically, this makes racing feel even more urgent: falling behind today might mean permanent disadvantage tomorrow.

Race dynamics make collective action and coordination feel impossible. Countries hesitate to implement strong safety regulations that might handicap their domestic AI industries. Companies resist voluntary safety commitments unless competitors make identical pledges. Everyone waits for others to move first, creating gridlock even when all parties privately acknowledge the risks. The result is a lowest-common-denominator approach to safety that satisfies no one.

AI governance needs innovative approaches to break out of race dynamics. Traditional arms control offers limited lessons, since AI development happens in private companies, not government labs. We need new approaches (Trajano & Ang, 2023; Barnett, 2025). Several ideas have been proposed. Some examples are:

- Reciprocal snap-back limits. States publish caps on model scale, autonomous-weapon deployment and data-center compute that activate only when peers file matching commitments. The symmetry removes the fear of unilateral restraint and keeps incentives focused on shared security rather than zero-sum dominance (Karnofsky, 2024).

- Safety as a competitive asset. Labs earn market trust by subjecting frontier models to independent red-team audits, embedding provenance watermarks and disclosing incident reports. Regulation can turn these practices into a de-facto licence to operate so that “secure by design” becomes the shortest route to sales (Shevlane et al., 2023; Tamirisa et al., 2024).

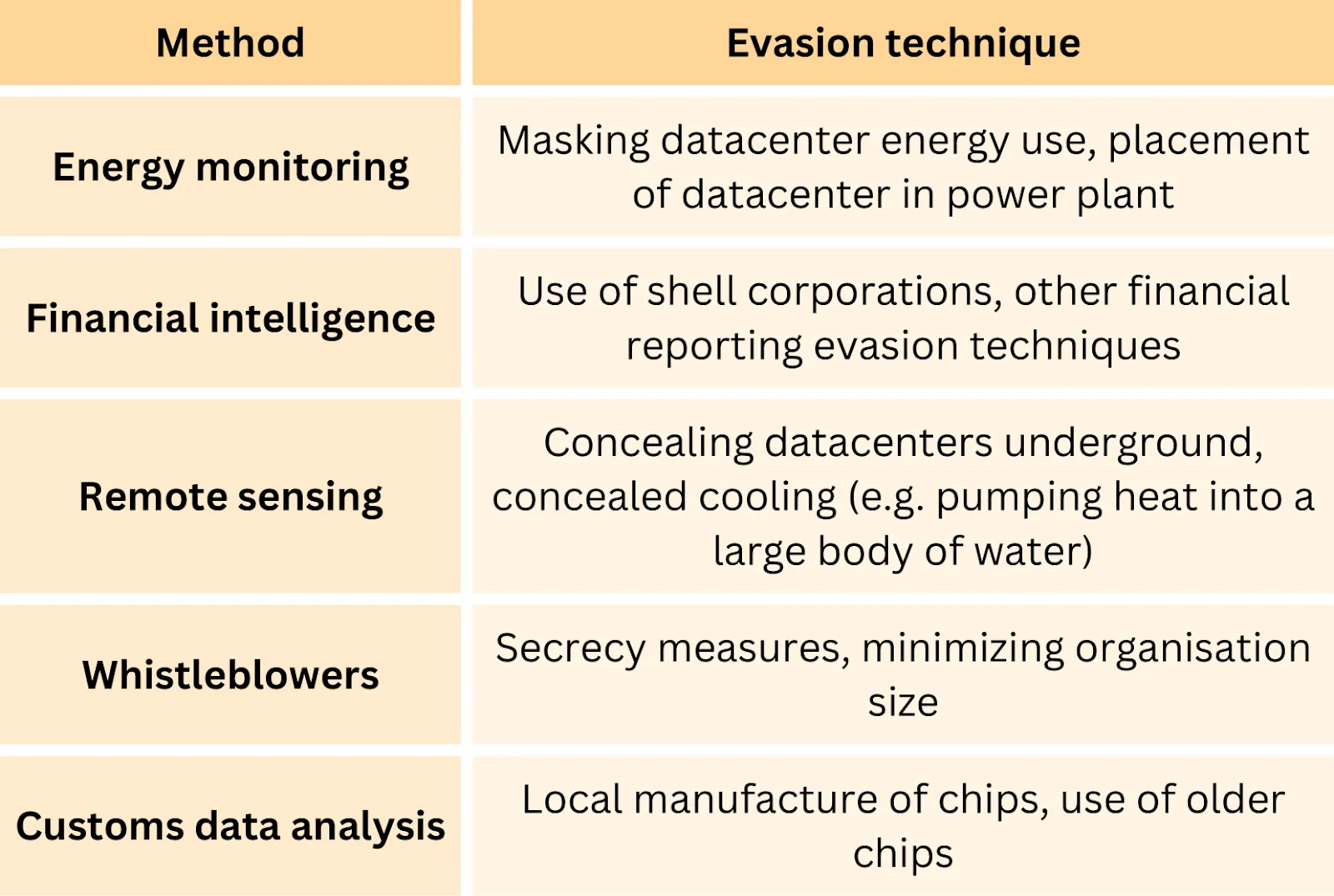

- Containment. Export controls on advanced chips; API-only access with real-time misuse monitoring; digital forensics; and Know-Your-Customer checks slow the spread of dangerous capabilities even as beneficial services stay widely available. These measures address open publication, model theft, talent mobility and hardware diffusion; factors that let a single leak replicate worldwide within days (Shevlane et al., 2023; Seger, 2023; Nevo et al., 2024).

- Agile multilateral oversight with a coordinated halt option. A lean UN-mandated body (think about it like a CERN or an IAEA-for-AI) needs the authority to impose emergency pauses when red-lines are crossed, backed by chip export restrictions and cloud-provider throttles that make a global “off switch” technically credible (Karnofsky, 2024; Petropoulos et al., 2025).

- Secret-safe verification. Secure enclaves, tamper-evident compute logs and zero-knowledge proofs let inspectors confirm that firms observe model and data controls without exposing weights or proprietary code, closing the principal oversight gap identified in current treaty proposals (Shevlane et al., 2023; Wasil et al., 2024; Anderljung et al. 2024).

Proliferation #

AI capabilities propagate globally through digital networks at speeds that render traditional control mechanisms largely ineffective. Unlike nuclear weapons that require specialized materials and facilities, AI models are patterns of numbers that can be copied and transmitted instantly. Let's think about this scenario - a cutting-edge AI model, capable of generating hyper-realistic deepfakes or designing novel bioweapons, is developed by a well-intentioned research lab. The lab, adhering to principles of open science, publishes their findings and releases the model's code as open-source. Within hours, the model is downloaded thousands of times across the globe. Within days, modified versions start appearing on code-sharing platforms. Within weeks, the capabilities that were once confined to a single lab have proliferated across the internet, accessible to anyone with a decent computer and an internet connection. This scenario, while hypothetical, isn't far from reality. This fundamental difference makes traditional non-proliferation approaches nearly useless for AI governance.

Multiple channels enable rapid proliferation:

- Open publication accelerates capability diffusion. The AI research community's commitment to openness means breakthrough techniques often appear on arXiv within days of discovery. What took one lab years to develop can be replicated by others in months. Meta's release of Llama 2 led to thousands of fine-tuned variants within weeks, including versions with safety features removed and new dangerous capabilities added (Seger, 2023).

- Model theft presents growing risks. As AI models become more valuable, they become attractive targets for malicious hackers and criminal groups. A single successful breach could transfer capabilities worth billions in development costs. Even without direct theft, techniques like model distillation can extract capabilities from API access alone (Nevo et al., 2024).

- Talent mobility spreads tacit knowledge. When researchers move between organizations, they carry irreplaceable expertise. The deep learning diaspora from Google Brain and DeepMind seeded AI capabilities worldwide. Unlike written knowledge, this experiential understanding of how to build and train models can't be controlled through traditional means (Besiroglu, 2024).

- Hardware proliferation enables distributed development. As AI chips become cheaper and more available, the barrier to entry keeps dropping. What required a supercomputer in 2018 now runs on hardware costing under 100,000 dollars. This democratization means dangerous capabilities become accessible to ever-smaller actors (Masi, 2024).

AI proliferation poses unique challenges - digital goods follow different rules than physical objects. Traditional proliferation controls assume scarcity: there's only so much enriched uranium or only so many advanced missiles. But copying a model file costs essentially nothing. Once capabilities exist anywhere, preventing their spread becomes a battle against the fundamental nature of information. It's far easier to share a model than to prevent its spread. Even sophisticated watermarking or encryption schemes can be defeated by determined actors.

Verifying that someone if not developing harmful AI capabilities is extremely hard. Unlike nuclear technology where detection capabilities roughly match proliferation methods, AI governance lacks comparable defensive tools (Shevlane, 2024). Nuclear inspectors can use satellites and radiation detectors to monitor compliance. But verifying that an organization isn't developing dangerous AI capabilities would require invasive access to code, data and development: practices likely revealing valuable intellectual property. Many organizations thus refuse intrusive monitoring (Wasil et al., 2024). This would require a combination of many different technical, and national measures.

Dual-use nature complicates controls. The same transformer architecture that powers beneficial applications can also enable harmful uses. Unlike specialized military technology, we can't simply ban dangerous AI capabilities without eliminating beneficial ones. This dual-use problem means governance must be far more nuanced than traditional non-proliferation regimes (Anderljung, 2024). A motivated individual with modest resources can now fine-tune powerful models for harmful purposes. This democratization of capabilities means threats can emerge from anywhere, not just nation-states or major corporations. Traditional governance frameworks aren't designed for this level of distributed risk.

How can governance help slow AI proliferation? Several potential solutions have been proposed to find the right balance between openness and control:

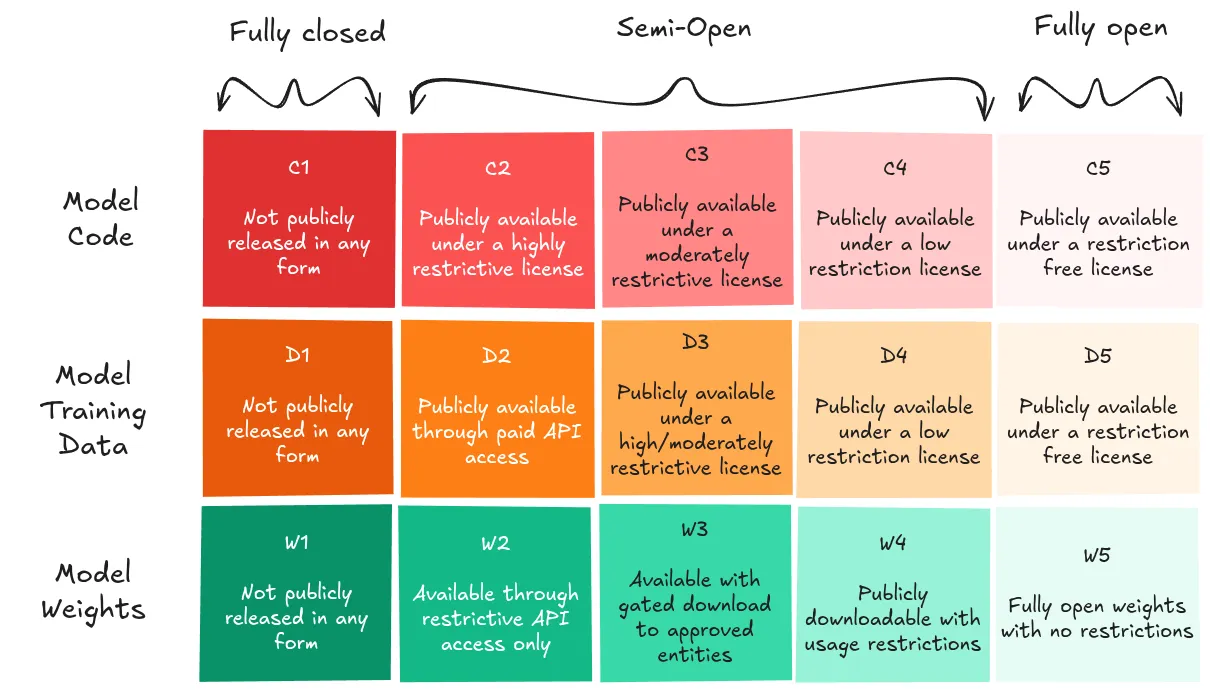

- Targeted openness. Publish fundamental research but withhold model weights and fine-tuning recipes for high-risk capabilities, keeping collaboration alive while denying turnkey misuse (Seger, 2023).

- Staged releases. Roll out progressively stronger versions only after each tier passes red-team audits and external review, giving society time to surface failure modes and tighten safeguards before the next step (Solaiman, 2023).

- Enhanced information security. Treat frontier checkpoints like crown-jewel secrets: hardened build pipelines, model-weight encryption in use and at rest, and continuous insider-threat monitoring (Nevo et al., 2024).

- Export controls and compute access restrictions. Block shipment of the most advanced AI accelerators to unvetted end-users and require cloud providers to gate high-end training clusters behind Know-Your-Customer checks (O’Brien et al., 2024).

- Responsible disclosure. Adopt cybersecurity-style norms for reporting newly discovered “dangerous capability routes,” so labs alert peers and regulators without publishing full exploit paths (O’Brien et al., 2024).

- Built-in technical brakes. Embed jailbreak-resistant tuning, capability throttles and provenance watermarks that survive model distillation, adding friction even after weights leak (Dong et al., 2024).

Uncertainty #

The exact way the post-AGI world will look is hard to predict — that world will likely be more different from today's world than today's is from the 1500s [...] We do not yet know how hard it will be to make sure AGIs act according to the values of their operators. Some people believe it will be easy; some people believe it'll be unimaginably difficult; but no one knows for sure.

Expert predictions consistently fail to capture AI's actual trajectory. If you read media coverage of ChatGPT — which called it ‘breathtaking’, ‘dazzling’, ‘astounding’ — you’d get the sense that large language models (LLMs) took the world completely by surprise. Is that impression accurate? Actually, yes. (Cotra, 2023) GPT-3's capabilities exceeded what many thought possible with simple scaling. Each major breakthrough seems to come from unexpected directions, making long-term planning nearly impossible (Gruetzemacher et al., 2021; Grace et al., 2017). The "scaling hypothesis" (larger models with more compute reliably produce more capable systems) has held surprisingly well. But we don't know if this continues to AGI or hits fundamental technical or economic limits. This uncertainty has massive governance implications. If scaling continues, compute controls remain effective. If algorithmic breakthroughs matter more, entirely different governance approaches are needed (Patel, 2023).

Risk assessments vary by orders of magnitude. Some researchers assign negligible probability to existential risks from AI, while others consider them near-certain without intervention, reflecting fundamental uncertainty about AI's trajectory and controllability. When experts disagree this dramatically, how can policymakers make informed decisions? (Narayanan & Kapoor, 2024).

Capability emergence surprises even developers. Models demonstrate abilities their creators didn't anticipate and can't fully explain (Cotra, 2023). If the people building these systems can't predict their capabilities, how can governance frameworks anticipate what needs regulating? This unpredictability compounds with each generation of more powerful models (Grace et al., 2024). Traditional policy-making assumes predictable outcomes. Environmental regulations model pollution impacts. Drug approval evaluates specific health effects. But AI governance must prepare for scenarios ranging from gradual capability improvements to sudden recursive self-improvement.

Waiting for certainty means waiting too long. By the time we know exactly what AI capabilities will emerge, it may be too late to govern them effectively. Yet acting under uncertainty risks implementing wrong-headed policies that stifle beneficial development or fail to prevent actual risks. This creates a debilitating dilemma for conscientious policymakers (Casper, 2024).

How can governance operate under uncertainty? Adaptive governance models that could keep pace with rapidly changing technology could offer a path forward. Rather than fixed regulations based on current understanding, we need frameworks that can evolve with our knowledge. This might include:

- Regulatory triggers based on capability milestones rather than timelines

- Sunset clauses that force regular reconsideration of rules

- Safe harbors for experimentation within controlled environments

- Rapid-response institutions capable of updating policies as understanding improves

Building consensus despite uncertainty requires new approaches. Traditional policy consensus emerges from shared understanding of problems and solutions. With AI, we lack both. Yet somehow we must build sufficient agreement to implement governance before capabilities outrace our ability to control them. This may require focusing on process legitimacy rather than outcome certainty agreeing on how to make decisions even when we disagree on what to decide.

Accountability #

[After resigning from OpenAI] These problems are quite hard to get right, and I am concerned we aren't on a trajectory to get there [...] OpenAI is shouldering an enormous responsibility on behalf of all of humanity. But over the past years, safety culture and processes have taken a backseat to shiny products. We are long overdue in getting incredibly serious about the implications of AGI.

A small number of actors make decisions that affect all of humanity. The CEOs of perhaps five companies and key officials in three governments largely determine how frontier AI develops. Their choices about what to build, when to deploy, and how to ensure safety have consequences for billions who have no voice in these decisions. OpenAI's board has fewer than ten members. Anthropic's Long-Term Benefit Trust controls the company with just five trustees. These tiny groups make decisions about technologies that could fundamentally alter human society. No pharmaceutical company could release a new drug with such limited oversight, yet AI systems with far broader impacts face minimal external scrutiny. Nearly all frontier AI development happens in just two regions: the San Francisco Bay Area and London. The values, assumptions, and blind spots of these tech hubs shape AI systems used worldwide, yet we know more about how sausages are made than how frontier AI systems are trained. What seems obvious in Palo Alto might be alien in Lagos or Jakarta, yet the global majority have essentially no input into AI development (Adan et al., 2024).

Traditional accountability mechanisms don't apply. Corporate boards nominally provide oversight, but most lack the incentives to evaluate systemic AI risks. Government regulators struggle to keep pace with rapid development. Academic researchers who might provide scientific evidence and independent assessment often depend on corporate funding or compute access. The result is a governance vacuum where no one has both the capability and authority needed for proper governance (Anderljung, 2023). The consequences of this lack of governance are already becoming apparent. We've seen AI-generated deepfakes used to spread political misinformation (Swenson & Chan, 2024). Language models have been used to create convincing phishing emails and other scams (Stacey, 2025). When models demonstrate concerning behaviors, we can't trace whether they result from training data , reward functions, or architectural choices. This black box nature of development is a big bottleneck in accountability (Chan et al., 2024).

Power and Wealth Concentration #

AI concentrates power in unprecedented ways. AI systems, especially those developed by dominant corporations, are reshaping societal power structures. These systems determine access to information and resources, effectively exercising automated authority over individuals (Lazar, 2024). As these systems become more capable, this concentration intensifies. The organization that first develops AGI could gain decisive advantages across every domain of human activity, a winner-take-all dynamic with no historical precedent.

Wealth effects compound existing inequalities. AI automation primarily benefits capital owners while displacing workers, deepening existing disparities. Recent empirical evidence suggests that AI adoption significantly increases wealth inequality by disproportionately benefiting those who own models, data, and computational resources, at the expense of labor (Skare et al., 2024). Without targeted governance interventions, AI risks creating never before seen levels of economic inequality, potentially resulting in the most unequal society in human history (O’Keefe, 2020).

Democratic governance faces existential challenges. When information itself is controlled by private entities, traditional democratic institutions struggle to remain effective (Kreps & Kriner, 2023). Some empirical evidence indicates that higher levels of AI integration correlate with declining democratic participation and accountability, as elected officials find themselves unable to regulate complex technologies that evolve faster than legislative processes (Chehoudi, 2025). This emerging technocratic reality fundamentally undermines democratic principles regarding public control and oversight.

International disparities threaten global stability. Countries without domestic AI capabilities face permanent subordination to AI leaders. AI adoption significantly exacerbates international inequalities, disproportionately favoring technologically advanced nations. This disparity threatens not only economic competitiveness but also basic sovereignty when critical decisions are effectively outsourced to foreign-controlled AI systems (Cerutti et al., 2025). We have no agreed frameworks for distributing AI's benefits or managing its disruptions. Should AI developers owe obligations to displaced workers? How should AI-generated wealth be taxed and redistributed? What claims do non-developers have on AI capabilities? These questions need answers before AI's impacts become irreversible, yet governance current discussions barely acknowledge them (Ding & Dafoe, 2024).

Was this section useful?

Thank you for your feedback

Your input helps improve the Atlas.