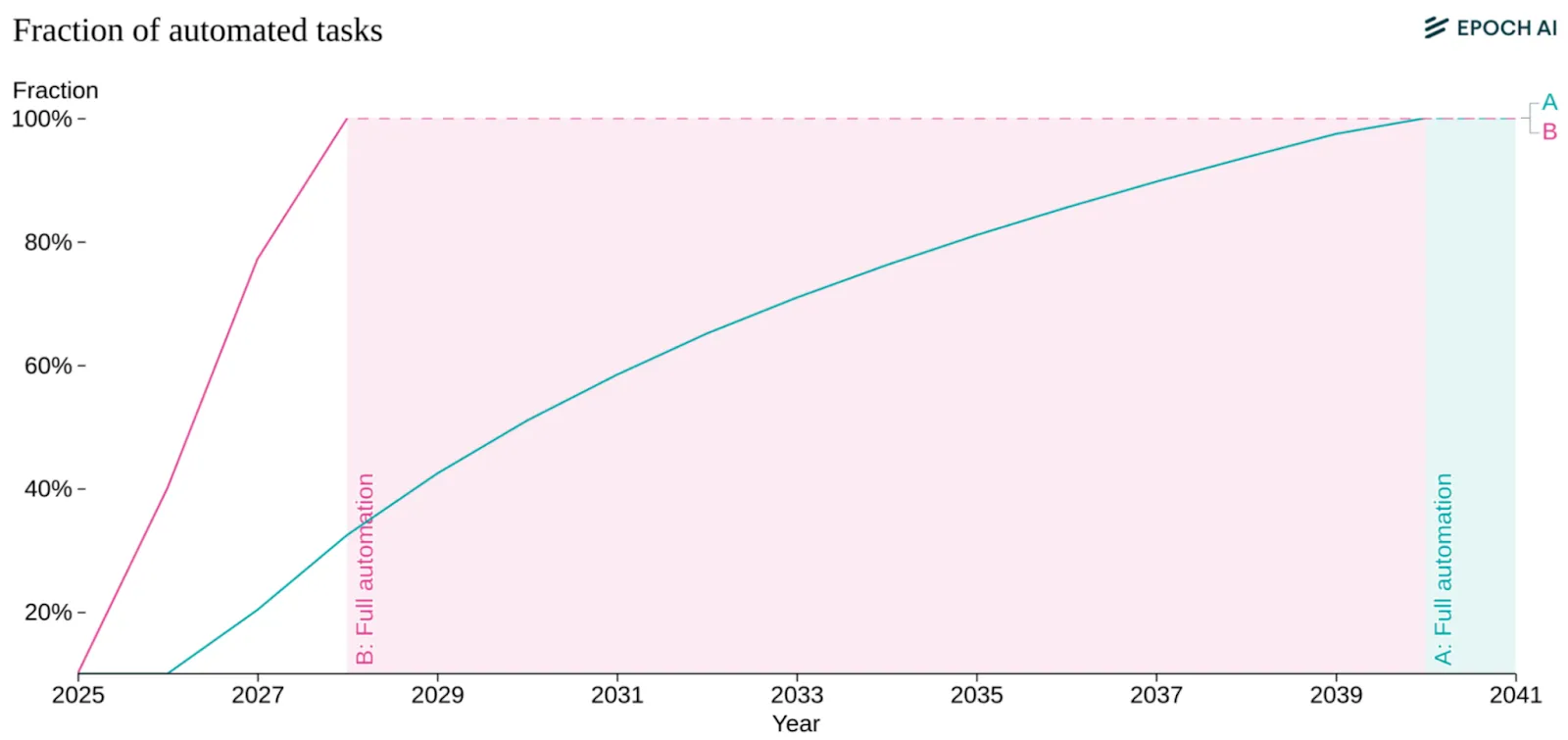

Predicting when AI automates cognitive labor determines which safety strategies are viable. The difference between 10 years and 50 years fundamentally changes which safety strategies are viable and which risks demand immediate attention . If TAI is able to automate cognitive labor (and thereby automate ML RnD) by 2030, we need safety solutions working soon. There's no time for slow theoretical research—we need approaches that work with current systems and scale quickly. If it arrives around 2050, we have breathing room for fundamental alignment research, for building robust governance frameworks, and for developing evaluation methods we can trust.

This section presents empirical trends and forecasts of AI progress using data-driven analysis. Our goal is to build on the scaling laws discussion and present the strongest available evidence so you can form informed views on where AI might be headed. We focus primarily on compute-based trends, with heavier quantitative forecasts presented alongside graphs. An appendix covers judgment-based surveys and expert opinions. Remember the old saying: "All models are wrong, but some are useful."

Forecasting helps us form internally consistent beliefs about different possible futures. The way that you should think about forecasting methods is not as concrete predictions of timelines; but instead as scenarios that help you reason about different potential futures. They let you check if your beliefs are internally coherent. If you think investment grows 5x per year AND software efficiency improves 3x per year AND hardware scales 15% per year AND each order of magnitude automates at least 10% of tasks, then what does that imply? Is the outcome of this combination consistent with the future you expect? If you're surprised, maybe one of your input beliefs needs updating.

Current evidence suggests scaling can continue through at least 2030. Training compute has grown 5x per year since 2020, dataset sizes have grown by 3.7x/year, and training costs by 3.5x/year. As a concrete example, this means that in mid 2025 the cost of training a single AI model (Grok-4) including hardware and electricity, is estimated at $480 million USD (Epoch AI, 2025). By 2030, this trajectory points to a single training run requiring hundreds of billions of dollars and gigawatts of power - which is comparable to running a small city (Owen, 2025). These are unprecedented scales, but analysis suggests that they aren't impossible (Epoch AI, 2025; Sevilla et. al., 2024; Owen, 2025). The question is whether the economic incentives justify it and whether the infrastructure constraints (chips, power, data, … ) can be overcome in time.

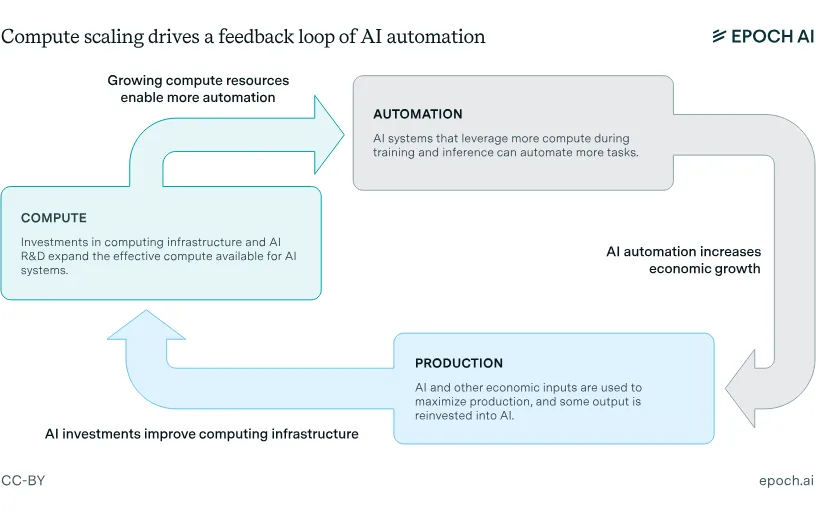

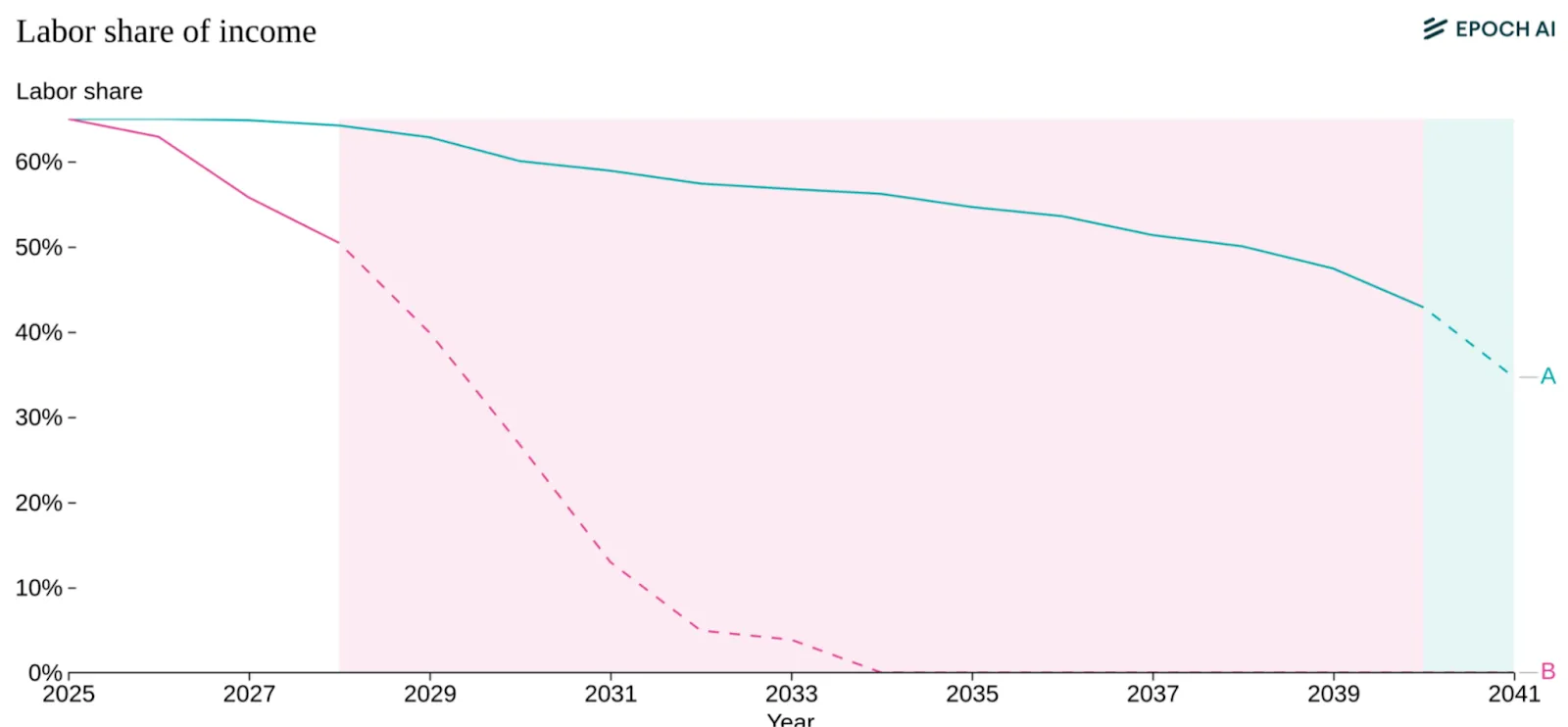

AI systems that leverage more compute during training and inference are capable of automating progressively more tasks. Initially, only a small fraction of tasks are automated, so running AI systems creates relatively little economic value. 6 Once effective compute budgets grow large enough, the range of automated tasks expands until eventually all cognitive labor becomes automated. This feedback loop—compute enabling automation, which increases productivity, which funds more compute—continues until full labor automation.

The path to full labor automation runs through three resources: compute, data, and the economic returns that fund both. In the subsections below, we examine each constraint. For compute, we look at effective FLOP growth—the combination of more chips, better algorithms, and more efficient hardware. For data, we track when we exhaust the internet's text and what happens after. Each section answers: does this constraint stop scaling before 2030? The appendix provides detailed breakdowns of the other relevant factors like investment trends, semiconductor production, and power infrastructure for readers who want the full picture.

All forecasts come with wide error margins that compound over time. Even if we assume compute-based scaling laws hold, we still don't know how much compute TAI will actually require. One framework for estimating the compute required for general intelligence uses "biological anchors," treating the human brain as a proof of concept. These estimates vary dramatically depending on the biological process used as a reference: a lower bound considers the compute performed in learning skills during a human lifetime (~ FLOP), while a theoretical upper bound accounts for the total compute performed in shaping humans over evolutionary history (~ FLOP) - twelve orders of magnitude of uncertainty (Carlsmith, 2020; Cotra, 2020; Ho, 2022). It’s like not knowing if something costs one dollar or a trillion dollars. When someone says "AGI in 2045," they mean "somewhere in the 2030s-2050s range, with 2045 as a rough center" - not a precise date. The same principle applies to all trends and forecasts presented through this section; for example, projections of available chips range by a factor of 20×, and some compute estimates span 50× (Sevilla et al., 2024).

Effective Compute #

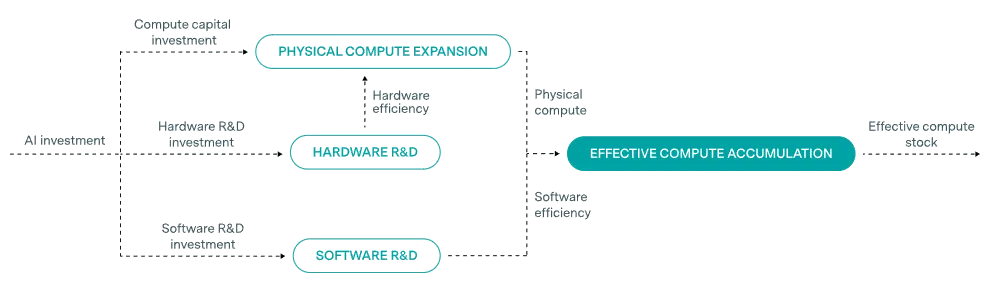

Effective compute combines three independent factors that each multiply your AI capabilities. Scaling laws track performance against compute, but "compute" means more than just counting GPUs. When researchers say GPT-4 used more compute than GPT-3, they're not just talking about running more hardware for longer. They're talking about the growth in ‘effective’ compute measured in ‘effective’ floating-point operations (eFLOPs). As an analogy, think of it like measuring how far a fleet of cars can travel. You need three things: how many cars you have (chip production), how fast each car goes (hardware efficiency), and how efficiently you're driving (software efficiency) (Erdil et al., 2025). The relationship looks like this:

As an illustrative example, think about wanting to train a model that gets 90% accuracy on some benchmark. In 2020, that might have required 1 billion FLOP using the algorithms available then. But by 2025, better training methods, hardware utilization and other algorithmic improvements mean you only need 100 million FLOP to hit that same 90% accuracy. Your software got 10× more efficient. Better algorithms multiply your effective compute without building a single new chip. Meanwhile, the physical efficiency of your chips got better too. A 2025 GPU does more FLOP per dollar than a 2020 GPU - that's hardware efficiency. And you're also just making more chips overall as more investment keeps flowing in. So the total “effective” FLOPs changes as a function of all three of these variables.

Each factor can improve independently, which is why effective compute grows faster than any single input. You can build more chips without improving their speed. You can develop better software to make use of existing hardware. You can design faster processors without changing either your software or building more chips. When all three improve simultaneously—as they have been—the total compute available (effective compute) compounds much faster than hardware trends alone would suggest. Here's are the trends for each in 2025 (Epoch AI, 2025), with more details in the appendix:

- Hardware efficiency: GPU performance grows at 1.35x per year. Each new chip generation does more FLOP/s for the same cost.

- Algorithmic efficiency: Software improvements cut the compute needed for a given result by ~3x per year. Better training methods mean you need less hardware to hit the same benchmark.

- Chip production: The number of AI chips produced has grown 2.3x per year since 2019, driven by semiconductor fab expansions and massive capital investment.

Training Data #

Besides just effective compute, the second overarching factor that we have to take into consideration is the amount of available data to train on.

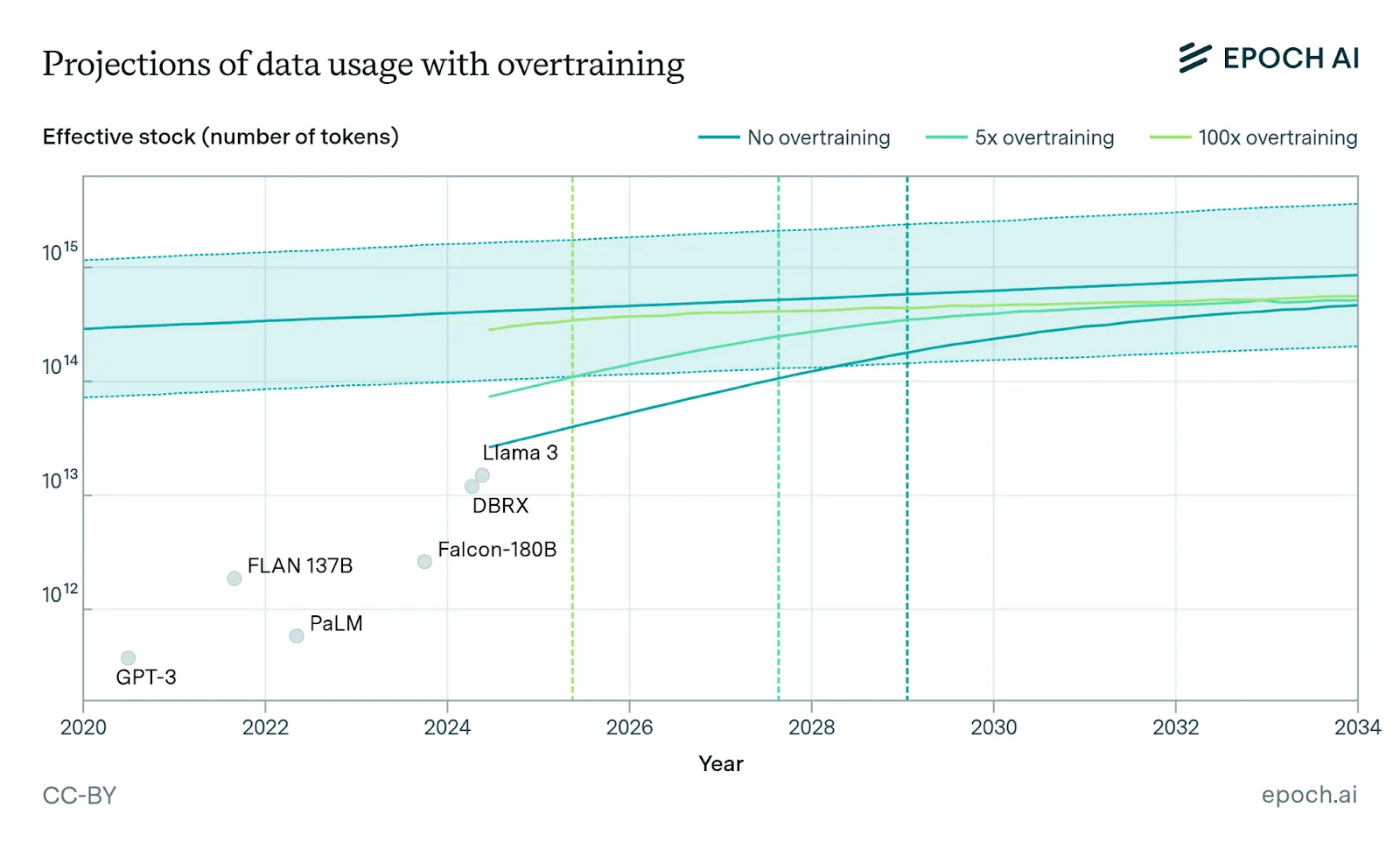

The training dataset size for language models has grown by 3.7x per year since 2010. The internet has maybe 30 years worth of text data at current consumption rates—but we'll hit that wall around 2028. The indexed web contains roughly 500 trillion tokens of text (after removing duplicates). The largest models in 2024 train on about 15 trillion tokens. If we keep scaling at 4× per year, projections say that we will exhaust high-quality public text data between 2026 and 2032 (Epoch AI, 2023; Villalobos et al., 2024). Three escape routes exist, whether data actually constrains scaling through 2030 depends on how well these alternatives work.:

- Multimodal data: The internet has ~10 trillion images and ~10 trillion seconds of video. If encoded efficiently, this could 3-10x the effective data supply.

- Synthetic data: AI-generating it’s own training data removes the constraint entirely—if the outputs are high enough quality. Post-training methods like reinforcement learning on reasoning tasks already demonstrate this works for some domains.

- Task-based learning: Self-play reinforcement learning can generate training data through environment interaction. This means AIs can learn without human-generated pretraining examples as long as tasks can be formalized as games with explicit rules and success metrics (like Go or Chess). For example, AlphaZero learned superhuman strategies without any human gameplay examples, using only the game rules and billions of self-played matches. In principle, this approach could be extended to teaching any arbitrary task allowing for data free learning through self-play on specified tasks. This is still very speculative, it requires simulation environments encoding task dynamics, explicit reward functions, and tractable state spaces.

Footnotes

-

You can think of a task as a specific unit of work or activity that a worker performs as part of their job (for instance tasks for a factory worker may include operating machinery, inspecting products, and coordinating with team members). Some tasks are assumed to be harder to automate than others, as they require more training and runtime compute to be effectively automated.

↩

Was this section useful?

Thank you for your feedback

Your input helps improve the Atlas.