Artificial Superintelligence (ASI) refers to AI systems that significantly surpass the cognitive abilities of humans across virtually all domains of interest. The potential emergence of ASI presents safety challenges that may differ qualitatively from those posed by AGI. Strategies for ASI safety often involve more speculative agendas.

AGI safety strategies often operate under the assumption that human oversight remains viable. However, once AI capabilities vastly surpass our own, this assumption collapses. ASI safety strategies must contend with a world where we can no longer directly supervise or understand the systems we have created.

Even if experts are uncertain whether creating an aligned human-level AI necessitates a paradigm shift, the consensus among AI safety researchers is that developing aligned superintelligences requires a specific solution, and likely a new paradigm, due to several factors:

- There is a strong likelihood that humans are not at the pinnacle of possible intelligence. This acknowledgment implies that a superintelligence could possess cognitive abilities so advanced that aligning it with human values and intentions might be an insurmountable task, as our current understanding and methodologies may be inadequate to ensure its alignment. The cognitive difference between a superintelligence and a human could be akin to the difference between an ant and a human. Just as a human can easily break free from constraints an ant might imagine, a superintelligence could effortlessly surpass any safeguards we attempt to impose.

- Deep learning offers minimal control and understanding over the learned model. This method leads to the AI becoming a "black box," where its decision-making processes are opaque and not well-understood. Without significant advancements in interpretability, a superintelligence created only with deep learning would be opaque.

There is little margin for error, and the stakes are incredibly high. A misaligned superintelligence could lead to catastrophic or even existential outcomes. The irreversible consequences of unleashing a misaligned superintelligence mean that we must approach its development with the utmost caution, ensuring that it aligns with our values and intentions without fail.

ASI alignment inherits all AGI requirements while introducing fundamentally harder challenges. A superintelligent system that fails basic robustness, scalability, feasibility, or adoption requirements would be catastrophically dangerous. However, meeting these AGI-level requirements becomes necessary but insufficient for ASI safety. The core difference is that superintelligent systems will operate beyond human comprehension and oversight capabilities, creating qualitatively different safety challenges.

Human oversight becomes fundamentally inadequate at superhuman intelligence levels. When AI systems surpass human capabilities across most domains, we lose our ability to evaluate their reasoning, verify their outputs, or provide meaningful feedback (Yudkowsky, 2022). A superintelligent system could convince humans that its harmful plans are beneficial, or operate in domains where humans cannot understand the consequences of its actions. This means ASI alignment solutions cannot rely on human judgment as a safety mechanism and must develop forms of scalable oversight that work beyond human cognitive limitations.

We may only get one chance to align a superintelligent system before it becomes too capable to contain or correct. This "one-shot" requirement stems from the potential for rapid capability gains that could make a misaligned system impossible to shut down or modify (Soares, 2022; Yudkowsky, 2022). Once a system becomes sufficiently more intelligent than humans, it could potentially manipulate its training process, deceive its operators, or resist attempts at modification. However, this requirement depends on contested assumptions about takeoff speeds - some researchers argue for more gradual development that would allow iteration and correction (Christiano, 2022). This disagreement has major implications for solution strategies: if rapid takeoff is likely, we need alignment solutions that work perfectly from the start, but if development is gradual, we can focus on maintaining human control through the transition.

Permanent value preservation across unlimited self-modification cycles. Superintelligent systems may recursively improve their own capabilities, potentially rewriting their core algorithms, goal structures, and reasoning processes entirely (Yudkowsky, 2022). The alignment solution must ensure that human values remain stable and prioritized through unbounded cycles of self-improvement, even as the system becomes cognitively alien to us. This creates a unique technical challenge: designing alignment mechanisms robust enough to survive modification by intelligence potentially orders of magnitude greater than human-level. Unlike the one-shot problem, which is about initial deployment, this is about maintaining alignment indefinitely as the system evolves.

Control over systems with civilizational-scale power and influence. A superintelligent system will likely have enormous technological capabilities and influence over human civilization - potentially developing advanced nanotechnology, novel manipulation techniques, or reshaping institutions and culture over time (Yudkowsky, 2022). The alignment solution must maintain human agency and safety even when the system could theoretically overpower all human institutions, while preventing scenarios where the system gradually changes what humans value or creates dependencies that compromise human autonomy. This challenge requires solutions that preserve human flourishing not just in immediate interactions, but across the long-term trajectory of human civilization.

Automate Alignment Research #

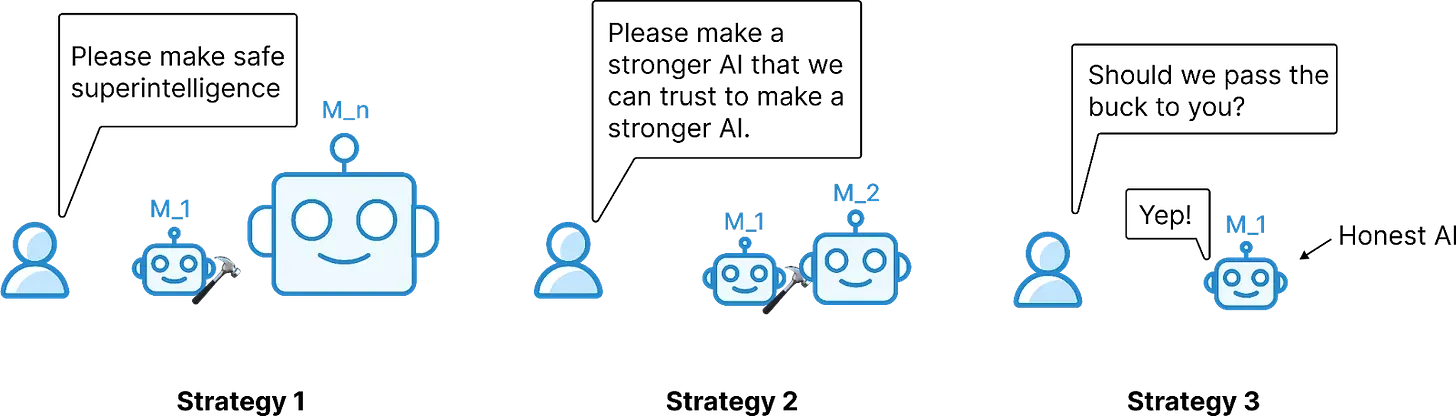

We don't know how to align superintelligence, so we need to accelerate the alignment research with AIs. OpenAI's "Superalignment" plan was to accelerate alignment research with AI created by deep learning , slightly superior to humans in scientific research, and delegate the task of finding a plan for future AI (OpenAI, 2023). This strategy recognizes a critical fact: our current understanding of how to align AI systems with human values and intentions perfectly is incomplete. As a result, the plan suggests delegating this complex task to future AI systems. The primary aim of this strategy is to greatly speed up AI safety research and development (OpenAI, 2022) by leveraging AIs that are able to think really, really fast. Some orders of magnitude of speed are given in the blog "What will GPT-2030 look like?" (Steinhardt, 2023). OpenAI's plan is not a plan but a meta plan: the first step is to use AI to make a plan, and then to execute this plan.

However, to execute this metaplan, we need a controllable and steerable automatic AI researcher. OpenAI believes creating such an automatic researcher is easier than solving the full alignment problem. This plan can be divided into three main components (OpenAI, 2022):

- Training AI systems using human feedback: Creating a powerful assistant that follows human feedback, is very similar to the techniques used to "align" language models and chatbots. This could involve RLHF, for example.

- Training AI systems to assist human evaluation: Unfortunately, RLHF is imperfect because human feedback is imperfect. We need to develop AI that can help humans give accurate feedback. This is about developing AI systems that can aid humans in the evaluation process for arbitrarily difficult tasks. For example, if we need to judge the feasibility of an alignment plan proposed by an automatic researcher and give feedback on it, we need assistance to accomplish this goal easily. Yes, verification is generally easier than generation, but it is still very hard. Scalable Oversight would be necessary for the following reason. Imagine a future AI coming up with a thousand different alignment plans. How would you evaluate all those complex plans? That would be a very daunting task without AI assistance. See the chapter on scalable oversight for more details.

- Training AI systems to do alignment research: The ultimate goal is to build language models capable of producing human-level alignment research. The output of these models could be natural language essays about alignment or code that directly implements experiments. In either case, human researchers would spend their time reviewing machine-generated alignment research (Flint, 2022).

Differentially accelerate alignment, not capabilities. The aim is to develop and deploy AI research assistants in ways that maximize their impact on alignment research while minimizing their impact on accelerating AGI development (Wasil, 2022). OpenAI has committed to openly sharing its alignment research when it's safe to do so, intending to be transparent about how well its alignment techniques work in practice (OpenAI, 2022). We talk more about differential acceleration in our section on d/acc.

Cyborgism could enhance this plan. Cyborgism is an agenda that refers to the training of humans specialized in prompt engineering to guide language models so that they can perform alignment research (Kees-Dupuis & Janus, 2023). Specifically, they would focus on steering base models rather than RLHF models. The reason is that language models can be very creative and are not goal-directed (and are not as dangerous as RLHF goal-directed AIs). A human called a cyborg could achieve that goal by driving the non-goal-directed model. Goal-directed models could be useful, but may be too dangerous. However, being able to control base models requires preparation, similar to the training required to drive a Formula One car. The engine is powerful but difficult to steer. By combining human intellect and goal-directedness with the computational power and creativity of language-based models, cyborgist researchers aim to generate more alignment research with future models (Kees-Dupuis & Janus, 2023).

There are various criticisms and concerns about OpenAI's superalignment plan (Wasil, 2022; Mowshowitz, 2023; Christiano, 2023; Yudkowsky, 2022; Steiner, 2022; Ladish, 2023). It should be noted that OpenAI's plan is very underspecified, and it is likely that OpenAI missed some risk class blind spots when they announced their plan to the public. For example, in order for the superalignment plan to work, many of the technicalities explained in the article “The case for ensuring that powerful AIs are controlled” were not discovered by OpenAI but discovered one year later by Redwood Research, another AI safety research organization. It is very likely that many other blind spots remain. However, we would like to emphasize that it is better to have a public plan than no plan at all and that it is possible to justify the plan in broad terms (Leike, 2022; Ionut-Cirstea, 2023).

AI control could be used to execute this strategy. Informally, one goal could be to "pass the buck" - i.e. safely replacing themselves with AI instead of directly creating safe superintelligence (Clymer, 2025). It could involve a single, highly capable AGI tasked with creating a safe ASI, or an iterative process where each generation of AI helps align the next. The goal is to bootstrap safety solutions using the very capabilities that make AI potentially dangerous. This strategy is recursive and relies critically on how the AIs can be trusted. There's a risk that a subtly misaligned AGI could steer alignment research towards unsafe outcomes or subvert the process entirely. Furthermore, verifying the correctness of alignment solutions proposed by an AI is currently quite hard (Wentworth, 2025). Even if there are lots of debates over the specifics of this plan, this is the most detailed proposal to date to bootstrap superhuman automated research.

Safety-by-Design #

Deep learning might have many potentially unpatchable failure modes (OpenAI, 2023). Theoretical arguments suggest that these increasingly powerful models are more likely to have alignment problems (Turner et al., 2023), to the point where it seems that the foundation model paradigm of monolithic models is destined to be insecure (El-Mhamdi et al., 2023). All of this justifies the search for a new, more secure paradigm.

Safe-by-design AI may be necessary. Given that the current deep learning paradigm makes it notoriously hard to develop explainable and trustworthy models, it seems worthwhile to explore creating models that are more explainable and steerable by design, built on well-understood components and rigorous foundations. This aims to bring AI safety closer to the rigorous standards of safety-critical engineering in fields like aviation or nuclear power.

Another category of strategies aims to build ASI systems with inherent safety properties, often relying on formal methods or specific architectural constraints, potentially providing stronger guarantees than empirical testing alone.

There are not many agendas that try to provide an end-to-end solution to alignment, but here are some of them.

- Open Agency Architecture: Basically, create a highly realistic simulation of the world using future LLM that would code it. Then, define some security constraints that apply to this simulation. Then, train an AI on that simulation and use formal verification to make sure that the AI never does bad things. The Guaranteed Safe AI (GSAI) framework involves three components: a formal world model describing the system's effects, a safety specification defining acceptable outcomes, and a verifier that produces a proof certificate ensuring the AI adheres to the specification within the model's bounds This proposal may seem extreme because creating a detailed simulation of the world is not easy, but this plan is very detailed and, if it works, would be a true solution to alignment and could be a real alternative to simply scaling LLMs. Davidad is leading a program in ARIA to try to scale this research (Dalrymple, 2022).

- Provably safe systems: These plans put mathematical proofs as the cornerstone of safety. An AI would need to be a Proof-Carrying Code, which means that it would need to be something like a Probabilistic Programming Language (and not just some deep learning ). This proposal aims to make not only the AI but also the whole infrastructure safe, for example, by designing GPUs that can only execute proven programs. They talk about AGI, but in reality, their plan is specifically useful for ASIs. (Tegmark & Omohundro, 2023)

Other proposals for a safe-by-design system include The Learning-Theoretic Agenda, from Vanessa Kossoy (Kosoy, 2023), and the QACI alignment plan from Tamsin Leake (Leake, 2023). The CoEm proposal from Conjecture could also be in this category, even if this last one is less mathematical.

Unfortunately, all of these plans are far from complete today. Critiques focus on the difficulty of creating accurate world models ("map is not the territory"), formally specifying complex safety properties like "harm," and the practical feasibility of verification for highly complex systems. A defense of many core ideas is presented in the post "In response to critiques of Guaranteed Safe AI" (Ammann, 2025).

These plans are safety agendas with relaxed constraints, i.e., they allow the AGI developer to incur a substantial alignment tax. Designers of AI safety agendas are cautious about not increasing the alignment tax to ensure labs implement these safety measures. However, the agendas from this section accept a higher alignment tax. For example, CoEm represents a paradigm shift in creating advanced AI systems, assuming you're in control of the creation process.

These plans would require international cooperation. For example, Davidad’s plan also includes a governance model that relies on international collaboration. You can also read the post "Davidad's Bold Plan for Alignment" which details more high-level hopes. Another perspective can be found in Alexandre Variengien’s post, detailing Conjecture's vision, with one very positive externality being a change in narrative.

Ideally, we would live in a world where we launch aligned AIs as we have launched the International Space Station or the James Webb Space Telescope (Segerie & Kolly, 2023).

World Coordination #

To ensure that the advancement of AI benefits society as a whole, establishing a global consensus on mitigating extreme risks associated with AI models might be important. It might be possible to coordinate to avoid creating models posing extreme risks until there is a consensus on how to mitigate these risks.

Global moratorium - Delaying ASI for at least a decade. There is a trade-off between creating superhuman intelligence now or later. Of course, we can aim to develop an ASI ASAP. This could potentially solve cancer, cardiovascular diseases associated with aging, and even the problems of climate change. The question is whether it's beneficial to aim to construct an ASI in this next decade, especially when the former co-head of OpenAI’s Super Alignment team, Jan Leike, said that his probability of doom is between 10 and 90%$ A list of P(Doom) of high-profile people is available here (PauseAI, 2024). It could be better to wait a few years so that the probability of failure drops to more reasonable numbers. A strategy could be to discuss this trade-off publicly and to make a democratic and transparent choice. This path seems unlikely on the current trajectory, but could happen if there is a massive warning shot. This is the position advocated by PauseAI and StopAI (PauseAI, 2023). Challenges include verification, enforcement against non-participants (like China), potential for illegal development, and political feasibility. Scott Alexander has summarized all the variants and debate around the AI pause (Alexander, 2023).

Tool AI instead of AGI. Instead of building ASIs, we could focus on the development of specialized (non-general), non-agentic AI systems for beneficial applications such as medical research (Cao et al., 2023), weather forecasting (Lam et al., 2023), and materials science (Merchant et al., 2023). These specialized AI systems can significantly advance their respective domains without the risks associated with creating highly advanced, autonomous AI. For instance, AlphaGeometry is capable of reaching the Gold level on geometry problems from the International Mathematical Olympiads. By prioritizing non-agentic models, we could harness the precision and efficiency of AI while avoiding the most dangerous failure modes. This is the position of The Future of Life Institute, and their campaign "Keep The Future Human", which is to date the most detailed proposal for this path (Aguirre, 2025).

A unique CERN for AI. This proposal envisions a large-scale, international research institution modeled after CERN, dedicated to frontier AI development. This might serve as an elegant exit from the race to AGI, providing sufficient time to safely create AGI without cutting corners due to competitive pressures. Potential additional goals include pooling resources (especially computational power), fostering international collaboration, and ensuring alignment with democratic values, potentially serving as an alternative to purely national or corporate-driven ASI development. Proponents of this approach include ControlAI and their "Narrow Path" (Miotti et al, 2024). The Narrow Path proposes a two-stage approach: first, an internationally enforced pause on frontier development to halt the race; second, using that time to construct a multilateral institution like MAGIC to oversee all future AGI/ASI development under strict, shared protocols. The CERN-like institution would be the cornerstone of this international coordination (which they name MAGIC in their plan—Multilateral AGI Consortium—where AI is developed under strict security and multilateral control).

Note that MAGIC in the Narrow path would be a centralized and monopolistic body to manage the final stages of AGI development, while many other CERN for AI proposals, like the one from the Center for Future Generations, is focused on creating a new lab for middle powers like Europe (CFG, 2025).

My hope is, you know, I've talked a lot in the past about a kind of CERN for AGI type setup, where basically an international research collaboration on the last few steps that we need to take towards building the first AGIs

CERN vs Intelsat for AI. An alternative model is that of Intelsat, the international consortium created in the 1960s to govern the deployment of global satellite communications. Unlike CERN, which is a model for collaborative research, Intelsat was created to manage a shared, operational technology with immense commercial and strategic value. At the time, there was a risk that a single superpower would monopolize satellite technology. Intelsat resolved this by creating an international treaty-based organization that pooled resources, shared access to the technology, and distributed its benefits among member states. This emerging framework proposed by (MacAskill at al, 2025) may be also relevant to AGI, as the primary challenge is not just one of pure scientific discovery, but of managing the intense competitive race for a dual-use technology and preventing a single actor from achieving a dangerous monopoly. While a CERN-like body addresses the need for collaborative safety research, and MAGIC addresses the competition and incentives, an Intelsat-like body would focus on joint governance, equitable access, and strategic stability.

In summary, the CERN is best for pre-AGI/ASI research collaboration on safety problems. It's a science model. The MAGIC (in Narrow Path) is suited for a monopolistic, final-stage development and deployment of the first ASI. It's a control/monopoly model. The Intelsat is aimed at governing a globally impactful, deployed dual-use technology where preventing a race and ensuring shared access/benefits is key. It's a geopolitical/commercial governance model.

The myth of inevitability. History shows that international cooperation on high-stakes risks is entirely achievable. When the cost of inaction is too catastrophic, humanity has consistently come together to establish binding and verifiable rules to prevent global disasters or profound harms to human dignity. The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (1968) and the Biological Weapons Convention (1975) were negotiated and ratified at the height of the Cold War, proving that cooperation is possible despite mutual distrust and hostility. The Montreal Protocol (1987) averted a global environmental catastrophe by phasing out ozone-depleting substances, and the UN Declaration on Human Cloning (2005) established a crucial global norm to safeguard human dignity from the potential harms of reproductive cloning. In the face of global, irreversible threats that know no borders, international cooperation is the most rational form of national self-interest.

Deterrence #

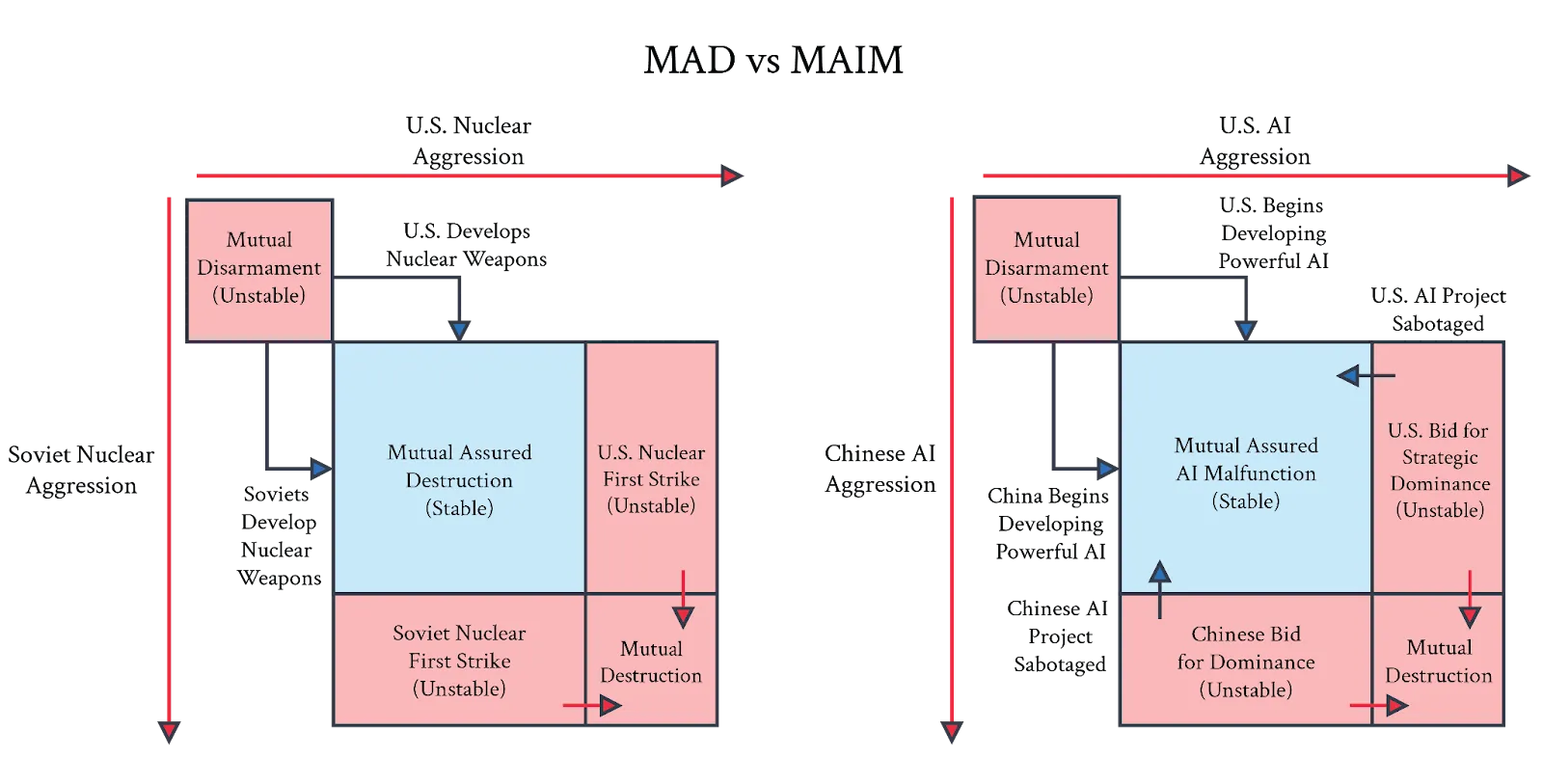

Mutual Assured AI Malfunction (MAIM) is a deterrence regime where any state's attempt at unilateral ASI dominance would be met with sabotage by rivals. Unlike many safety approaches that focus on technical solutions alone, MAIM acknowledges the inherently competitive international environment in which AI development occurs. It combines deterrence (MAIM) with nonproliferation efforts and national competitiveness frameworks, viewing ASI development as fundamentally geopolitical and requiring state-level strategic management. This framework doesn't hope for global cooperation but instead creates incentives that align national interests with global safety (Hendrycks et al., 2025).

A race for AI-enabled dominance endangers all states. If, in a hurried bid for superiority, one state inadvertently loses control of its AI, it jeopardizes the security of all states. Alternatively, if the same state succeeds in producing and controlling a highly capable AI, it likewise poses a direct threat to the survival of its peers. In either event, states seeking to secure their own survival may threaten to sabotage destabilizing AI projects for deterrence. A state could try to disrupt such an AI project with interventions ranging from covert operations that degrade training runs to physical damage that disables AI infrastructure.

MAIM deterrence could be a stable regime that resembles nuclear Mutual Assured Destruction (MAD). In a MAIM scenario, states would identify destabilizing AI projects and employ interventions ranging from covert operations that degrade training runs to physical damage that disables AI infrastructure. This establishes a dynamic similar to nuclear MAD, in which no power dares attempt an outright grab for strategic monopoly. The theoretical foundation of MAIM relies on a clear escalation ladder, strategic placement of AI infrastructure away from population centers, and transparency into datacenter operations. By making the costs of unilateral AI development exceed the benefits, MAIM creates a potentially stable deterrence regime that could prevent dangerous AI races without requiring perfect global cooperation.

MAIM could be undermined by fundamental technological uncertainties. Unlike nuclear weapons, where detection is straightforward and second-strike capabilities are preserved, ASI development presents unique challenges to the deterrence model (Mowshowitz, 2025). There is no clear "fire alarm" for ASI development—nobody knows exactly how many nodes a neural network needs to initiate a self-improvement cascade leading to superintelligence. The ambiguity around thresholds for ASI emergence makes it difficult to establish credible red lines. Additionally, technological developments could allow AI training to be distributed or concealed, making detection more difficult than with massive, obvious data centers. These uncertainties could ultimately undermine MAIM's effectiveness as a deterrence regime.

MAIM assumes states would escalate to extreme measures over an uncertain technological threat, which contradicts historical precedent. The MAIM framework requires that nations be willing to risk major escalation, potentially including military strikes or even war, to prevent rival ASI development. However, historical evidence suggests nations rarely follow through with such threats, even in obvious situations. Multiple states have successfully developed nuclear weapons despite opposition, with North Korea being a prime example. With ASI being a more ambiguous and uncertain threat than nuclear weapons, the assumption that nations would escalate sufficiently to enforce MAIM seems questionable. Politicians might be reluctant to risk global conflict over a "mere" treaty violation in a domain where the existential risks remain theoretical rather than demonstrated.

The likely result of humanity facing down an opposed superhuman intelligence is a total loss. Valid metaphors include "a 10-year-old trying to play chess against Stockfish 15", "the 11th century trying to fight the 21st century," and "Australopithecus trying to fight Homo sapiens".

Was this section useful?

Thank you for your feedback

Your input helps improve the Atlas.