Before we can discuss AI safety, we need to agree on what we mean by AGI. In our previous section on foundation models , we saw how modern AI systems are becoming increasingly powerful and general-purpose. But powerful at what, exactly? Some researchers claim we're already seeing "sparks" of AGI in the latest language models (Bubeck et al., 2023). Others predict human-level AI within a decade (Bengio et al., 2023). But human level at what exactly? How do we measure this? Without a clear definition, how do we assess such claims or plan appropriate safety measures?

If you can't define something, you can't measure it. If you can't measure it, you can't reliably track progress, identify or prepare for risks. Think about an example from physics. If we want to design and enforce speed limits for cars, saying something "moved 5" makes no sense without units. Did it move 5 meters, 5 feet, or 5 royal cubits? If we don't know how far or fast it moved, we can't enforce limits. The same applies to intelligence and subsequent safety measures. Every field needs standardized units - meters, watts, joules - to advance beyond vague descriptions. We need to treat AI safety with the same rigor to move past hand-waving about "intelligence."

Defining general intelligence is extremely challenging. Everyone agrees we need a definition to measure progress and design safety measures. So why don't we have one? The problem is that intelligence describes multiple overlapping abilities - problem-solving, learning, adaptation, abstract reasoning. Different disciplines view it through different lenses. Psychologists emphasize measurable cognitive skills. Computer scientists focus on task performance. Philosophers debate consciousness and self-awareness. Which approach matters most for AI safety? We go through a couple of case studies and previous attempts at a definition before giving the definitions we will be using for this text.

Case Studies #

Alan Turing suggested we could sidestep the whole mess by focusing on behavior. If a machine could imitate human conversation well enough to fool an interrogator, it should be considered intelligent (Turing, 1950). The behaviorist approach is simple - forget about internal mental states and focus on observable behavior. Can the system do the thing or not? Unfortunately, LLMs exposed some limitations to this approach. GPT-4 can pass Turing-style conversation tests while struggling with basic spatial reasoning or maintaining coherent long-term plans (Rapaport, 2020). The test was too narrow. Conversation is just one capability among many we care about. But Turing's core insight - focus on observable capabilities, not internal states - remains sound.

Consciousness based approaches to general intelligence focus on "true understanding." John Searle's Chinese Room argument suggested that systems might appear intelligent (stochastic parrots) without truly understanding - processing symbols without grasping their meaning (Searle, 1980). This view emphasizes internal cognitive states similar to human consciousness. The problem is that consciousness often proves even harder to define than intelligence. We are also unsure if intelligence and consciousness are necessarily linked - a system could potentially be highly intelligent without being conscious, or conscious without being particularly intelligent. AlphaGo is very intelligent within the context of playing Go, but it is clearly not conscious. A system doesn't need to be conscious to cause harm. Whether an AI system is conscious has little, if any, bearing on its ability to make high-impact decisions or take potentially dangerous actions. 3 Research into consciousness, sentience, and meta-ethical debates about the fundamental nature of intelligence are valuable, but less actionable for the type of safety work that this text focuses on.

Defining intelligence through goal achievement. Shane Legg and Marcus Hutter propose: "Intelligence measures an agent's ability to achieve goals in a wide range of environments" (Legg & Hutter, 2007). This captures something important - intelligent systems should be able to figure out how to get what they want across different situations. But it's too abstract for practical measurement. How are agents defined? Which goals? Which environments? How do you actually test this? The intuition is right, but we need something more concrete.

Process and adaptability focused views see intelligence as learning efficiency rather than accumulated skills. Some researchers define intelligence through adaptability: "the capacity of a system to adapt to its environment while operating with insufficient knowledge and resources" (Wang, 2020), or "the efficiency with which a system can turn experience and priors into skills" (Chollet, 2019). They argue that general intelligence is not demonstrated by the possession of a specific skill, but by the efficiency of acquiring new skills when faced with novel problems. High performance can be "bought" with sufficient data and compute, an AI that achieves superhuman performance at Go has mastered Go; it has not necessarily become more intelligent in a general sense. This makes sense - the ability to learn quickly from limited data in new situations matters. A system that needs a billion examples to learn what humans get from ten examples might be less impressive even if both reach the same final capability. But purely from a safety perspective, does the learning path matter more than the destination? If a system can perform dangerous tasks whether through efficient learning or brute-force memorization, the risks exist either way.

Psychologists use standardized tests and measure cognitive abilities directly. Psychometric traditions like the Cattell-Horn-Carroll (CHC) theory, break intelligence into measurable cognitive domains - reasoning, memory, processing speed, spatial ability (Schneider & McGrew, 2018). IQ tests aren't perfect, but they predict real-world outcomes better than vague philosophical debates about "true understanding." This benchmarking and test based framework gives us concrete domains to measure and track.

When discussing AI risks, talk about capabilities, not intelligence... People often have different definitions of intelligence, or associate it with concepts like consciousness that are not relevant to AI risks, or dismiss the risks because intelligence is not well-defined.

Behaviorist (capabilities focused) approaches matter most for safety. If an AI system can perform dangerous tasks at human-level or beyond - sophisticated planning, manipulation, deception - these risks exist regardless of how it achieved them. Did it learn efficiently or through brute force? Is it conscious or just pattern-matching? These questions don't change the risk profile. OpenAI defines AGI as "highly autonomous systems that outperform humans at most economically valuable work" (OpenAI, 2023). Anthropic frames their mission around ensuring "transformative AI helps people and society" (Anthropic, 2024). Both focus on what systems can do, and less on how they do it. But even these capability-based definitions can be too vague. Which humans are the measure - top experts or average workers? What counts as economically valuable - just current jobs or future ones? What about systems that excel at complex tasks but only work for short periods or require massive compute? The definitions point in the right direction but lack precision for tracking progress and identifying risks.

Our approach attempts to synthesize the useful parts of all these views. We adopt the behaviorist insight from Turing - primarily focusing on what systems can observably do. We use the psychometric tradition's concrete measurement framework from CHC theory. We acknowledge and incorporate the adaptability focused view's point about efficient learning but prioritize final capabilities. And we set aside the consciousness debate as not actionable for safety work.

We need a framework that's both concrete and continuous. Concrete enough to measure what systems can do right now while also being able to identify thresholds for regulation, and emerging risks before they materialize. It has to be continuous to capture progress along multiple dimensions rather than forcing everything into binary categories that lead to endless semantic debates about whether something "counts" as AGI. That's what we build in the next section: capability and generality as two continuous axes that let us describe any AI system precisely.

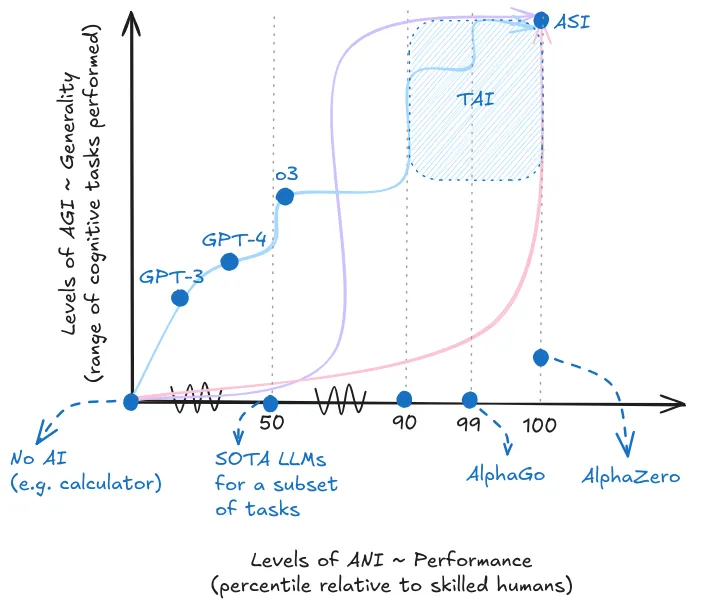

Defining General Intelligence #

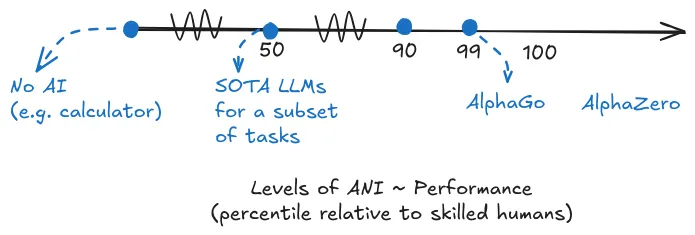

AGI exists on a continuous spectrum measured by two dimensions: capability and generality. Capability measures how well a system executes specific cognitive tasks - from 0% (can't do the task at all) to expert human level (outperforming roughly 80-90% of humans on that specific task) to superhuman (outperforming 100% of humans). Generality measures breadth - the percentage of cognitive domains where a system achieves expert-level capability. Together, these give us concrete statements like "our AI system can outperform 85% of humans in 30% of cognitive domains." This precisely describes any AI system's capabilities.

Capability measures depth - how good is the system at individual tasks. For decades, AI research focused on making systems excel at single tasks. Early chess programs in the 1950s beat novices but lost to experts. Deep Blue in the 1990s beat world champion Kasparov. AlphaGo in 2016 achieved superhuman capability at Go, a game humans thought computers wouldn't master for decades. This progression from "can't do the task" to "better than any human" represents the capability spectrum. Everything along this line - from basic competence to superhuman capability on a single task - counts as artificial narrow intelligence (ANI).

Capability alone isn’t enough to define and measure progress. AlphaGo achieved superhuman capability at Go - better than any human ever. Yet ask it to write a sentence, solve an algebra problem, or recognize objects in an image, and you get nothing. This is where foundation models changed things. The shift from building one narrow system per task to training general-purpose models is why we suddenly need a framework measuring both axes - capability and generality. Pre-foundation model AIs maxed out the capability axis on some individual tasks. But systems in the last few years are climbing both axes simultaneously - getting better at specific capabilities while also expanding to more domains. Capability measures depth; generality measures breadth.

When experts say they see "sparks of AGI" in recent systems, they're observing performance across multiple cognitive domains - not just one (Bubeck et al., 2023). Think of it like the first airplane built by the Wright brothers. It barely flew, stayed airborne for seconds, and looked nothing like modern airliners. But it was still a plane! Similarly, systems achieving expert-level performance across even a modest subset of cognitive domains represent genuine general intelligence - just early-stage (weak AGI). As these capabilities expand to cover more domains at higher performance levels, systems become both increasingly general and increasingly capable. There's no universally agreed upon threshold where "not AGI" suddenly becomes "AGI."

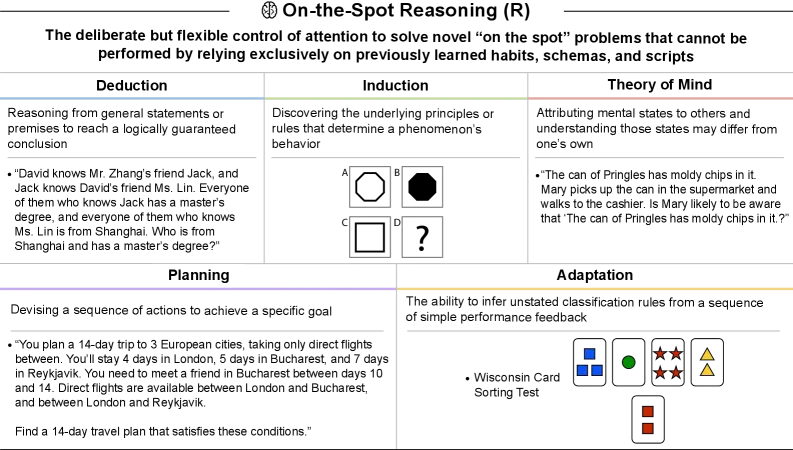

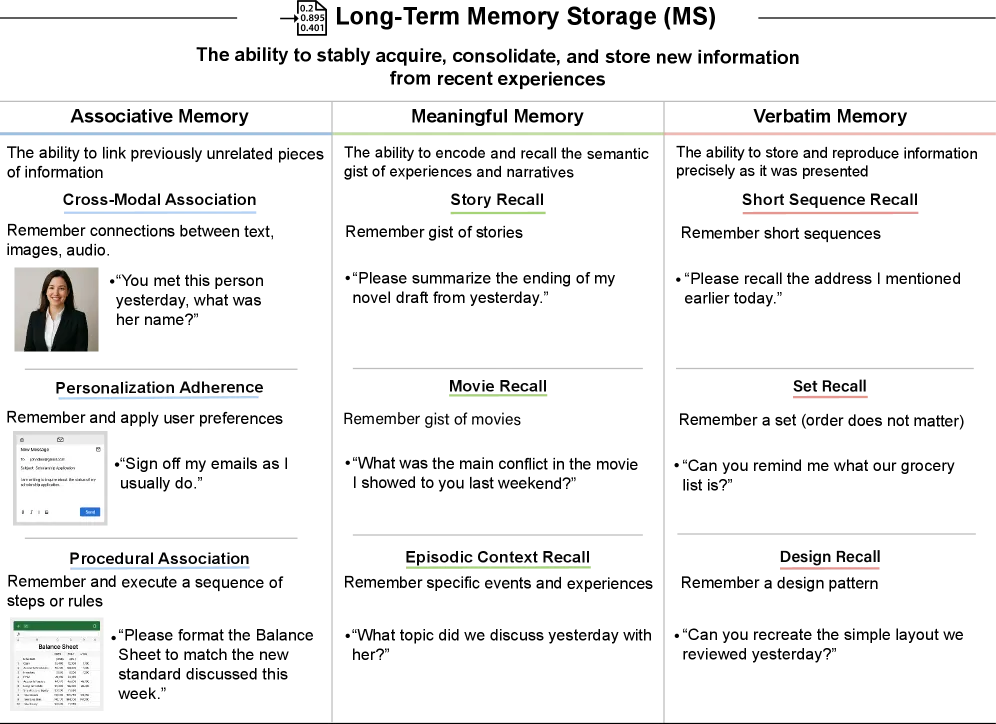

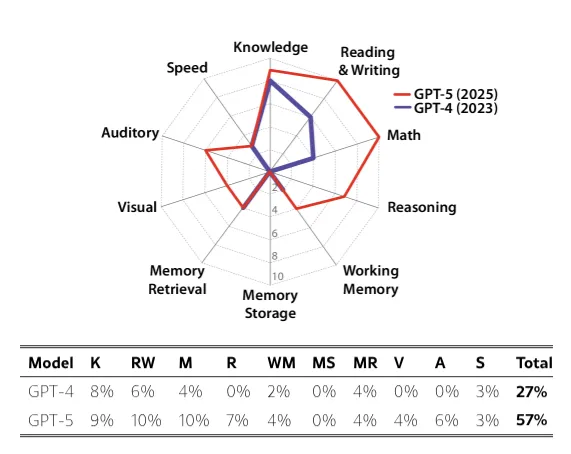

Not every possible task matters equally for progress towards general intelligence. We don't care much if AI gets better at knitting sweaters, but we care a lot if it improves at abstract reasoning, long-term planning, and memory. The things we care about can be informally thought of as everything that can be done as remote work on a computer. More formally, the domains we choose to focus on are non-embodied cognitive tasks. These break down into ten core capabilities from the Cattell-Horn-Carroll theory (Hendrycks et al., 2025). The specific capabilities we gave examples of in the first section - LLMs doing reasoning and math, vision models understanding images, agents planning in Minecraft - map directly onto these domains (Hendrycks et al., 2025):

- General Knowledge (K): The breadth of factual understanding of the world, encompassing commonsense, culture, science, social science, and history.

- Reading and Writing Ability (RW): Proficiency in consuming and producing written language, from basic decoding to complex comprehension, composition, and usage.

- Mathematical Ability (M): The depth of mathematical knowledge and skills across arithmetic, algebra, geometry, probability, and calculus.

- On-the-Spot Reasoning (R): The flexible control of attention to solve novel problems without relying exclusively on previously learned schemas, tested via deduction and induction.

- Working Memory (WM): The ability to maintain and manipulate information in active attention across textual, auditory, and visual modalities.

- Long-Term Memory Storage (MS): The capability to continually learn new information (associative, meaningful, and verbatim).

- Long-Term Memory Retrieval (MR): The fluency and precision of accessing stored knowledge, including the critical ability to avoid confabulation (hallucinations).

- Visual Processing (V): The ability to perceive, analyze, reason about, generate, and scan visual information.

- Auditory Processing (A): The capacity to discriminate, recognize, and work creatively with auditory stimuli, including speech, rhythm, and music.

- Speed (S): The ability to perform simple cognitive tasks quickly, encompassing perceptual speed, reaction times, and processing fluency.

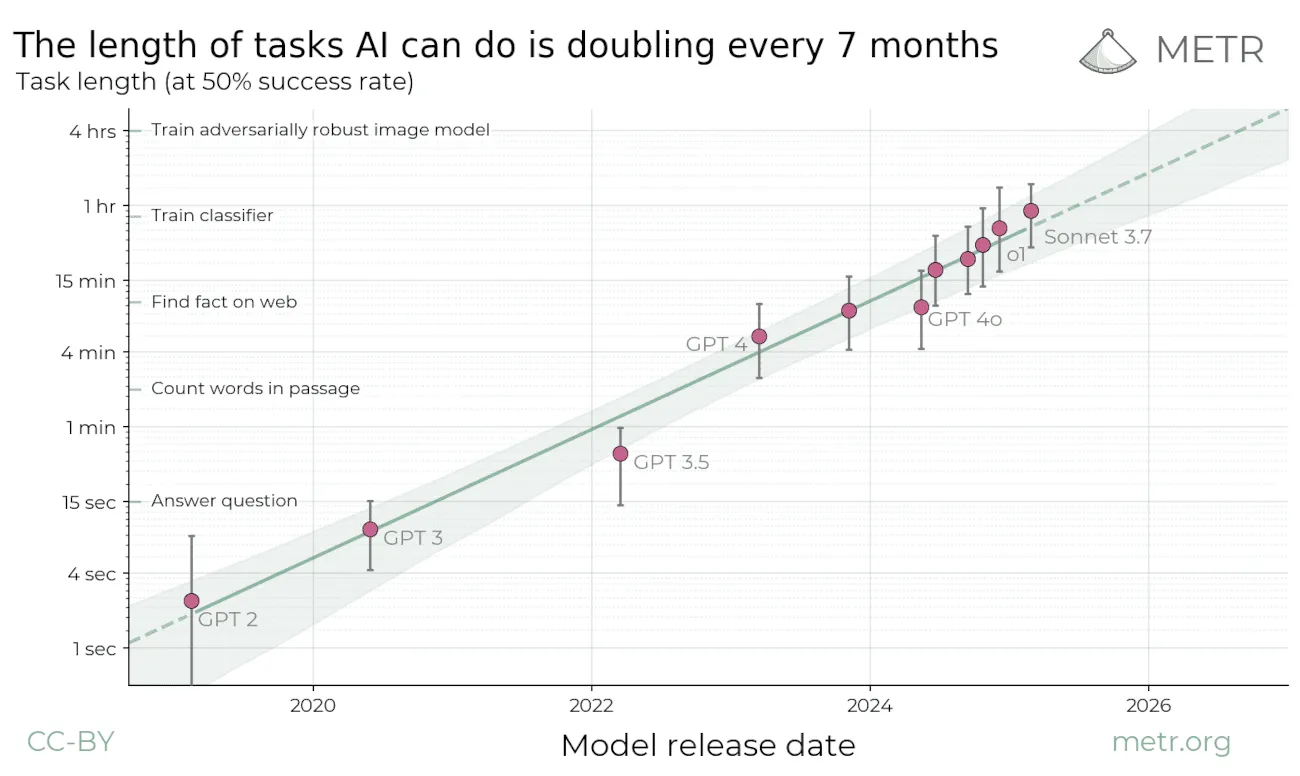

Generality is the percentage of these domains where a system achieves expert-level capability. If a system scores at the 80th percentile or higher on three out of ten domains, that's 30% generality. 4 Foundation models dramatically increased this compared to traditional narrow AI - one model handling writing, math, coding, and visual understanding represents unprecedented breadth. But current systems still cover only a fraction of cognitive capabilities, with particularly weak performance on long-term planning and memory-related domains (Hendrycks et al., 2025; Kwa et al., 2025).

Even though capability and generality exist on a continuum, certain thresholds still matter for safety planning. A system performing well on 50% of domains poses different risks than one excelling at 90%, we can't ignore this reality even if generality is a continuous variable. When pressed for concrete thresholds - which are often demanded in discussions - here's our interpretation of roughly how terms map onto the (performance, generality) space:

Our working definition does not include the autonomy with which an AGI system operates. This is a really important axis to pay attention to, but it has a higher bearing on deployment and impact rather than something inherent to a definition for AGI. It will be explored in the next chapter dedicated to risks from AI.

What we presented in this section is nowhere near a universally agreed upon definition. There are criticisms of both the levels of AGI framework, and of the CHC benchmark aggregation approach (Pacchiardi et al., 2025). There are many other alternative definitions and measurement frameworks in use like the European Commission's work on definition General Purpose AI (GPAI) models (EU Commission, 2025), the (t,n-AGI) framework (Ngo, 2023), OECD AI capability indicators (OECD, 2025), and not to mention all the competing definitions from the case studies in the previous sub-section. These are valid alternatives. The field is still evolving and finding gaps in its approach. We expect that the underlying benchmarks (which cognitive abilities are important?) and aggregation methods (how should we weigh them?) used to measure progress will continue to be debated but the underlying framework we teach in this section - of thinking of capability and generality as a continuous spectrum - will remain consistent.

The next sections of this chapter, look at why capabilities and generality have been improving rapidly in the recent years (Scaling), and what we can say about where they might be headed (Forecasting and Takeoff). Thinking about AI progress in this continuous way will help throughout this book when we discuss risks and mitigation strategies. Certain capability combinations might enable dangerous emergent behaviors even before reaching "human-level" on most tasks. Similarly governance frameworks, and clear policy communication depend on precise measurement to trigger appropriate responses. The rate of improvement along either axis provides important signals about which risks are most pressing, and which safety mitigations need to be developed.

Footnotes

-

We measure qualities like “sitational-awareness” in our chapters on risks, and evaluations using specific benchmarks. So we capture a model of the self and future planning, while distinguishing these aspects from conversations about consciousness.

↩ -

You can use expert-level parity (roughly 80-90th percentile human performance) as the threshold for "adequate" in measuring generality. Different researchers might set this threshold higher or lower depending on their specific concerns.

↩

Was this section useful?

Thank you for your feedback

Your input helps improve the Atlas.